Typically, the job of a city mayor involves chairing meetings, reviewing reports and participating in ribbon-cutting ceremonies. Try telling that to Eric Garcetti because back on a sunny day in August 2015, the mayor of Los Angeles was busy doing something a little different.

Mayor Garcetti Completes Shade Ball Cover of LA Reservoir by WeatherNation He tossed a load of big black balls into a lake! How many big black balls? By the time Garcetti had finished throwing in that batch, the total number clogging up the lake stood at

96 million! So, what exactly was he thinking? Maybe he was creating a giant black ball pit? Or trying to hide something beneath them?Whatever it is, it doesn’t exactly look like the most environmentally friendly activity. But crazy as it seems, Garcetti was actually putting the finishing touch on a massive project intended to save that body of water. Let's take a deep dive into why 96 million balls were dumped into that Los Angeles lake!

Los Angeles Reservoir

To start our story off, first we’ve got to find out what, and where, Eric Garcetti was throwing those balls into. The mayor was standing on the banks of Los Angeles’ Van Norman Reservoir also known simply as The Los Angeles reservoir. That basin, found in Sylmar, the most northern neighborhood in Los Angeles, stretches two-thirds of a mile long and nearly half a mile across.

In terms of overall size, the reservoir takes up a grand total of 175 acres! For context, that’s over 130 times the size of a football field! But how much water can it hold, exactly? Around, only some 3.3 billion gallons! That’s enough to fill some 5,000 Olympic swimming pools! Considering it holds so much water, the Los Angeles Reservoir is crucial for the city, as it can supply the city with 3-weeks of drinking water if it’s other resources fail. So not only is that place big, but it also provides an important backstop in LA’s water supply.

Considering just how important that reservoir is, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, or LADWP, must’ve been fearing the worst when a devastating drought hit the region back in 2011. The dry period was attributed to a ridge of high pressure in the Pacific Sea, known as the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge, which prevented winter storms from reaching California.As a result, less rainfall reached the area, with a 50% drop in precipitation from 2011 to 2012. To make things even more unbearable, the drought didn’t stop after a few months. In lasted for years! 2014 ended as California’s driest and warmest since records began in 1895, while in 2015, the state experienced it’s second driest and second warmest year on record!

The following year in 2016, conditions were so unbearable that some 62 million trees died in California alone. Unsurprisingly, that long-lasting drought wasn’t good news for Los Angeles’ water levels. Due to the drop in precipitation, less water ended up in rivers and streams. And so, less water ended up in the Los Angeles Reservoir. On top of that, the hot, dry conditions during that time also increased evaporation in bodies of water, which lowered the water levels even more, nowhere was that more obvious than at the reservoir. Things were so severe, it’s estimated the reservoir was losing around 300 million gallons of water each year! That’s more than 450 Olympic swimming pools! Yes, that means the reservoir was losing more than an Olympic swimming pool’s worth of water every single day to evaporation!

Bromate Issue

The humidity in that area must have been unbearable. But that historically dangerous drought wasn’t the only problem! Bromide is a naturally occurring element found in saltwater. On its own, it’s harmless to humans, but it doesn’t stay that way. The Los Angeles Reservoir, like many others, disinfects its water with a chlorine solution, making it safe for human consumption.

However, when chlorine is mixed with bromide, a nasty reaction takes place, turning the harmless bromide element into a much more sinister chemical compound called bromate. Bromate is a carcinogenic element, meaning that exposure to large amounts of the stuff can cause cancer. If that wasn’t scary enough, people who ingest large amounts of bromate may suffer from various gastrointestinal problems, like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain.

In some cases, individuals can even experience kidney problems, and hearing loss! So, that really isn’t something you want in your water! Understandably, the LADWP were keeping a close eye on bromate levels in all their reservoirs. And, much to their dread, the levels of the carcinogen compound in them kept spiking.Generally, water suppliers must keep bromate levels to a level below 10 parts per billion. But at the nearby Elysian Reservoir, back in 2007, bromate spiked to levels of 106 parts per billion. That’s over 10 times the maximum recommended concentration! Presumably, bromate levels at the Los Angeles Reservoir reached similarly scary heights.So, what was causing those uncontrollable spikes? Well, turns out bromide and chlorine weren’t the only things reacting in the reservoir. As it happens, sunlight turbo-charges that reaction, sending the bromate levels in the reservoir through the roof.

That left the LADWP with a difficult decision. Their water source contained bromide, which they couldn’t easily remove, and the water has to be chlorinated to make it safe for use. So, the only option they had left was to remove the sunlight!While it’s easy enough to block out the sun when you’re indoors, it’s not such a simple task when you’ve got to cover an area of 175 acres! Initially, it was thought that a large floating tarp cover could protect the reservoir from those sun rays. But making a tarp some half a mile wide just isn’t feasible, that project would be way too expensive, time consuming and from a physical standpoint, impossible!

An alternative method was suggested, which involved splitting the reservoir in two with a bisecting dam. That way, two floating covers could be installed more manageably. Yet, even then, that would cost a tear-jerking $300 million! Yes, safe to say it didn’t take long for that idea to be crossed off the list.

So floating covers may’ve been optimistic, but the LADWP weren’t finished there. They then came up with the idea of laying lots of high-density polyethylene pipes onto the reservoir. The thinking was the pipes would float on the water’s surface, creating some protection from the sun. The problem was, having enough pipes to cover such a sizeable body of water is both impractical and pricey.

Shade Balls

Despite plenty of plans and endless hours of meetings, the LADWP still couldn’t find a solution to their water worries. But speaking of balls, that leads us to the final proposal! After each plan fell flat on its face because of the cost and scale, a saving grace was found, the shade ball!

You might be thinking, what are shade balls? Maybe some kind of rare Poké Ball? Or even some dark derivation of baseball that you’ve somehow never come across? Sorry to disappoint but in reality, shade balls are simply those plastic, air-filled, black spheres.

Originally known as bird balls, those things were developed for the mining industry, where they were used to prevent birds from landing on toxic tailing ponds. From there, those bizarre balls were used at ponds near airport runways with the aim of deterring birds from the area, preventing them being minced by any airplane jet engines.Then, Brian White, a retired LADWP biologist, came up with the ingenious idea to use those bird balls for something else. He proposed for their use at reservoirs in Los Angeles, not to prevent birds from landing on the water, but to protect the fluid from sunlight.

Effectively, shade balls, or bird balls as they were then known, were a malleable cover that could be dumped onto the water’s surface, helping to decrease both water evaporation and bromate spikes! In 2008, Brian’s bright idea got the go-ahead, leading to 400,000 shade balls being dashed onto the Ivanhoe Reservoir in northern Los Angeles, with the primary aim of preventing bromate buildup.Clearly it caught on. Before long, two other Los Angeles reservoirs, Elysian and Upper Stone Canyon, also got their share of shade balls. But it wasn’t until 2015, 7 years after they were dumped into the Ivanhoe Reservoir, that the Los Angeles Reservoir gave that curious cover a chance. And it’s fair to say they more than made up for any lost time!In August of that year, Los Angeles mayor, Eric Garcetti, supervised the final load of shade balls being dumped into the reservoir. That final batch of 20,000 balls brought the total covering the Los Angeles Reservoir to a staggering 96 million! Can you imagine how long it took to dump all 96 million balls into the reservoir?

And with every inch of the water’s surface area covered, imagine taking a plunge in that water, you wouldn’t be able to move! Even driving a boat through that reservoir would be next to impossible! To get a feel of just how many balls were dumped into that reservoir, if you were to count each of those 96 million shade balls at 1 ball a second, it’d take you over 3 years until you tallied up every last one!Unsurprisingly, such a perplexing project immediately caught the eye of news outlets all over the world. The LA Reservoir’s decision to fill their water with those balls was covered everywhere from Buzzfeed to National Geographic. Within hours, videos of the shade balls were everywhere, the hashtag #shadeballs even went viral on social media!

While that’s all well and good, the thing everyone really wants to know is if those things actually worked. To explain, let’s first take a deeper dive into what we’re actually dealing with. Each one of the 96 million shade balls measures around 4 inches in diameter, making them slightly larger than a baseball.In terms of weight, they stack up at just under 1.5 ounces, which if you’re wondering is roughly a third of the weight of a baseball. For that reason, each and every one of the shade balls is partially filled with water, taking them to a heftier 8-ounce weight bracket, preventing them from blowing away in the wind.

And that’s quite important, considering they’re designed to sit on the reservoir’s surface and cast shade by, well, just staying there. By doing that the shade balls block direct sunlight from hitting the water. As a result, both the amount of evaporation and bromate levels drop.You may be wondering why exactly shade balls are coated black? If you listened in science class, you’ll know that the color black actually absorbs sunlight. After all, wouldn’t their dark color absorb more sunlight, forming a thermal blanket that’ll only help to speed up water evaporation at the reservoir?But, funnily enough, the balls dark hue is actually a measure to reduce evaporation. Now, the shade balls do absorb a lot of energy, getting hotter on the areas directly in the sunlight. However, as the balls are filled mostly with air, they’re good thermal insulators, meaning very little heat is transferred from the balls to the water below.

On the other hand, if the shade balls were white, they wouldn’t absorb the sunlight, but reflect it, allowing more light in the gaps between the balls, and as a result, allowing more light to hit the reservoir. If that wasn’t enough, shade balls are also dirt cheap! One of those balls costs just 36 cents! Obviously when you order 96 million that bill isn’t looking quite so measly. Added up the total cost of all the shade balls was over $34 million! While that sounds like a lot, considering the LADWP were considering forking out $300 million to fix their reservoir riddle, those shade balls are a steal at around a tenth of that price! On top of that, each shade ball is estimated to have a lifespan of around 10 years before needing to be replaced. That works out at a cost of just $3.4 million per year to protect the reservoir! Being cheap is all well and good. But we’ve still got to get to the crux of the matter. How effective were the shade balls at actually helping preserve the reservoir? Studies conducted on shade balls report that they reduce evaporation by 85-90%.

That equates to saving close to 300 million gallons of water every year, enough to provide drinking water for 8,100 people. More importantly, the shade provided by those millions of balls prevented sunlight from hitting the water and kick-starting the reaction that spiked bromate levels.While no figures have been released by the LADWP on the success of shade balls in limiting bromate levels in the LA reservoir, the shade ball’s ability to lower evaporation levels means less sunlight is hitting the water. And, as you’re now well aware, less sunlight equals less bromate!

Negative Effects

So, those 96 million shade balls reduced both evaporation and most likely bromate levels in the LA reservoir, providing safer water for millions of residents. And at a cheap price, relatively speaking! Sounds too good to be true and that’s because it was.

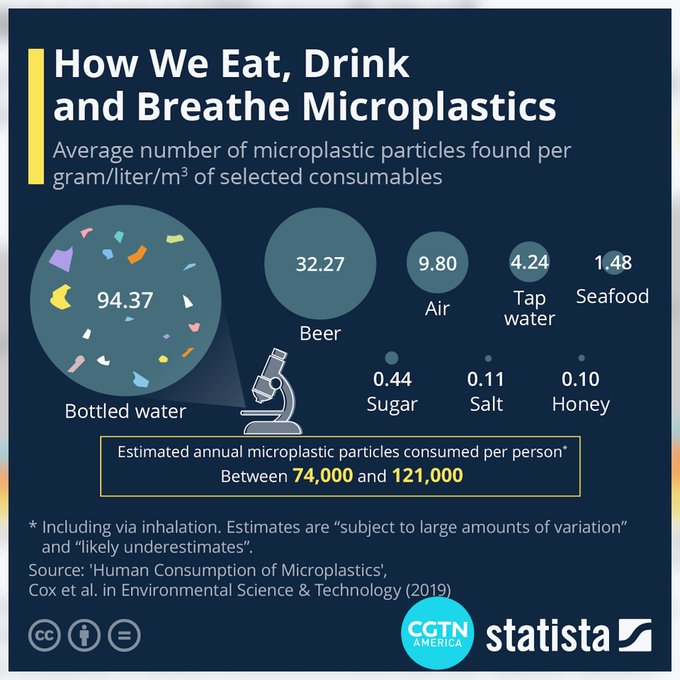

Firstly, those things may have some pretty nasty effects on the environment. On the face of it, shoving 96 million plastic balls into a reservoir doesn’t sound like the most climate-friendly activity. While each ball is made from high-density polyethylene, a fairly safe plastic, the stuff still isn’t fault-proof. Over time plastic degrades, especially when exposed to water and the baking hot sun. As a result, the shade balls leach, releasing microplastics into the water supply.

Most plastics found in our water supplies around the world start off as a typical objects like plastic bags, wrappers, water bottles, or even shade balls. Yet, overtime the plastic fragment into tiny microplastics. In fact, over 90% of the more than 5 trillion plastic pieces floating on the surface of the world’s oceans are smaller than a grain of rice. And what’s worse, the plastic takes hundreds of years to break down! In aquatic invertebrates, ingesting microplastics causes a decline in feeding behavior and fertility. In fish, microplastics can cause damaged to intestines, liver, gills and the brain. Us humans aren’t unaffected either. It’s reported that inhalation of microplastics can lead to respiratory problems, as well as fatigue and dizziness due to a low blood oxygen concentration. Can you imagine the potential microplastics released by some 96 million shade balls? Not sounding so great now, are they? But that’s not the only drawback. A research study published shortly after the shade balls were dumped into the LA reservoir revealed those spheres may actually use up more water than they save. Sounds crazy, because how exactly could they possible use more water than they save?

Shade balls have to be made in the first place, and that requires oil, gas and electricity to produce, all of which needs large amounts of water. It’s estimated that producing 96 million 4-inch shade balls would’ve used over 700 million gallons of water, more than double the amount that the shade balls were projected to save from evaporation each year!Stating that, it’s not all doom and gloom. If the shade balls were to last the 10 years that they’re said to, and save 300 million gallons of water each year, by the time they’re done with they’ll have saved 3 billion gallons of water! For reference, that’s more than 4 times the amount of water it took to manufacture them in the first place.So, while producing shade balls with masses of water seems counter-productive initially, those do technically make up for that loss in just over 2 years of their 10-year lifespan. Despite that, the negative effects of shade balls have been too much for some.By the end of 2015, the other 3 LA-Based shade supporters all had their balls removed. Ivanhoe Reservoir was going out of service, so the shade balls were obviously no longer needed. As for the Elysian and Upper Stone Canyon Reservoirs, well they opted for a standing floating cover in place of the shade balls.Unfortunately, as we’ve already learned, things could never be that easy for the Los Angeles Reservoir, with a floating cover costing some $300 million, the much cheaper shade balls offer a mid-term, cost-effective compromise. For some though, the black ball cover is really just a cheap way of avoiding getting into hot water, no pun intended!

Back in 2006, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Long-Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule announced that open-air reservoirs in the U.S holding treated water had to be covered. Some skeptics believe those black balls aren’t really there to prevent evaporation, or bromate build-up, but to stay in-compliance with the Environmental Protection Agency’s policy.

Either way, you won’t be surprised to know that Los Angeles isn’t the only place in the world that’s experienced water worries. All around the globe, there are some weird and wonderful water covers, designed to keep the sun away. Over in south Australia summer temperatures can climb above 110°F.So, in an attempt to ease water loss, the company

AgFloats came up with their own peculiar protection product. They used recycled tires to protect large bodies of water from sunlight! Saying that, have they not considered the fact tires have got a big round chunk missing from their middle? As well as that, AgFloats have also encountered the pesky problem that, when exposed to sunlight, their protective product will degrade, sending harmful residue into the water system. There are many environment friendly methods available to solve those water problems too. For example, floating aquatic plants, like water lilies, duckweed and water meal are helpful at reducing the evaporation of water reservoirs by covering the water’s surface, providing a layer of protection between air and the water’s surface.

Though it may sound good in practice, floating plants only reduce evaporation rates by up to 10%, making them 80% less effective than those trusty shade balls! As well as that, aquatic plants can lead to excessive algae growth. And, considering drinking algae-affected water can induce vomiting, diarrhea, fevers and headaches, that’s probably not something you want to be chugging down!

Shade Balls Should Not Be Balls

For all those weird and wonderful methods, as well as the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on creating the perfect cover to shade water from the Los Angeles Reservoir, there may be an even better solution out there. Presumably that’d be the product of a high-tech lab scientist, or some world-famous university lecturer? Not quite.

Instead, it was the work of a 10th grader! Yes, unbelievable as it sounds, Kenneth West from Melbourne High School, Florida, put forward his own

ingenious idea. After hearing about the shade balls, Kenneth realized that the balls, even when packed at their tightest, still exposed up to 10% of the water’s surface to the elements, increasing both evaporation and bromate levels.So, Kenneth thought of a way. What if there was another shape that could cover the water’s surface more compactly? And that brought him to the dodecahedron, a 12-sided dice like shape. Kenneth’s thinking was that those shapes, due to their pentagon faces would perfectly interlock with one another, forming a smooth seal over the water.

So, to test his theory, our boy Kenneth set up an experiment. He placed 12 bins in his yard and filled each with water. He then covered the water in 4 of the bins with a layer of standard shade balls. In another 4 bins he instead used the new shade dodecahedrons. And, finally in the last 4 bins he left the water completely exposed.Then, after 10 days Kenneth returned to his yard to assess the results. The bins with no cover lost 53% of their water to evaporation, on average. Bins that used shade balls fared much better, losing just 36% of their water. And, last but not least, bins that used dodecahedron lost less than 1% of their water! Thanks to their perfectly packed design, the shade dodecahedrons provided an almost perfect cover for the water, reducing evaporation by a staggering 99%!

So, could that be an answer for LA’s reservoirs? While Elysian and Upper Stone Canyon Reservoirs opted for floating covers, and the LA Reservoir continues to persist with its millions of shade balls, perhaps the perfect solution is those trusty shade dodecahedrons?

As they reduce evaporation by 99%, so those mini miracles will save almost a fifth more water compared to shade balls. Plus, as shade dodecahedrons would still cover the reservoir, they’d comply with the Environmental Protection Agency’s Long-Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule.

While shade balls have been removed from all but one of LA’s reservoirs, and more efficient alternatives have been created, multiple places around the world still opt for the use of Shade Balls. Take Yorkshire Water, in England for example.

Yorkshire Water Timelapse installing Shade Balls onto Lagoon by Euro-matic UK Ltd While England is pretty notorious for its abundance of rain, those balls aren’t used to keep water from evaporating. In that case, the balls are still used as Bird Balls, and as they perfectly disguise the water’s surface so that birds don’t land on it, while keeping the water beneath fit for purpose. I hope you were amazed at the analysis of when they dumped 96 million shade balls into the LA reservoir! Thanks for reading.

](https://beamazed.b-cdn.net/dfhvoxjgb/image/upload/v1716774701/things-real-estate-agents-dont-want-you-to-know/7AryMoPOy4rsTiLwDNjNdx.jpg?width=400)