Did you know that it’s almost guaranteed that every single species will eventually die out? In fact, scientists believe that 99% of all animals that have ever lived are now extinct. On the other hand, extinction isn’t as permanent as we thought. Through advances in biotechnology, there are some animals that are on the cusp of resurrection, and here are some unbelievable species that just might make a comeback.

Woolly Mammoth

You know how the ice caps are melting and we’re all totally doomed? Well, there might be an interesting solution to that: bring back the woolly mammoth! The gigantic creatures could grow up to 12 feet tall and weigh 8 tons that’s the weight of four and a half cars. Herds of mammoth were once widespread across the Mammoth Steppe grasslands that covered Europe, Asia, and North America.

We all know they’re neat, but how will the Woollies fight climate change? Across the Arctic tundra, there’s permafrost, ground that remains completely frozen for at least two years. But thanks to global warming permafrost has begun to thaw. When permafrost melts it releases carbon into the atmosphere, further accelerating the effects of climate change that will lead to mass extinction!

Geophysicist Dr. Sergey Zimov theorizes that if the tundra can be turned back to grassland like it would’ve been in the mammoth’s time, it could stop the permafrost from melting. Introducing big, grazing herbivores disturbs the ground and allows for deeper freezing of permafrost during the winter. When summer rolls around, the layer of grass insulates the permafrost, keeping it from melting.Bringing these beasts back is one mean feat, but Dr George Church feels up to the task. Church is a founder of the multi-million-dollar Texas-based company Colossal Biosciences, which plans to bring back all sorts of extinct creatures; and let’s hope they do better than

Jurassic Park. Church plans to

create an elephant-mammoth hybrid that will live in the Arctic Tundra. The animal wouldn’t exactly be a mammoth, it would only contain 1% mammoth DNA, making it more of an Arctic elephant that can comfortably survive in the tundra. For this they need mammoth DNA, which isn’t too tricky to get, considering the species vanished later than you probably think. The last herd only disappeared in 1650 BCE, that’s over a thousand years after the Pyramids of Giza were built!

The closest relative of the mammoth is the Asian elephant. Dr. Church will remove DNA from a female Asian elephant’s ovum and replace it with mammoth-like DNA. The elephant mammoth embryo will then be placed into an African elephant surrogate. Despite the difficulties of cloning and the moral objections some might have, Colossal claims they will have an elephant mammoth calf by 2027.

Tasmanian Tiger

Australia is home to some of the most wonderful fauna on the planet. Or rather, it was until the arrival of Europeans! Colonizers weren’t too kind to the region's wildlife, and one of the species they ended up wiping out was the thylacine.

Also known as the Tasmanian tiger and being a totally different species from the Tasmanian Devil, the carnivorous marsupial was once found across New Guinea, Australia, and South Tasmania. It was nocturnal, preying on kangaroos and other marsupials. Persecution of the thylacine started when farmers claimed that the animal killed their livestock, though the extent of this is likely exaggerated. In 1936 the last thylacine died due to neglect in Hobart Zoo and the species finally sputtered into a sad extinction.

Then things got worse. Removing an apex predator from an ecosystem has devastating effects on the environment, in a process called trophic downgrading. One thing thylacines did was keep illnesses under control by preying on sick and dying animals.After their extinction, diseases in the region became widespread, such as the horrible devil face tumor, which quickly spread through the Tasmanian Devil. Without predators, rodents and birds overgraze on vegetation leading to premature tree deaths and wildfires.

To top it all off, invasive species brought over by Europeans have grown out of control due to the lack of predators and prey on native species. As a result, more mammals have become extinct in Australia than in any other country, with 35% of all mammal extinctions being Australian.However, some believe that the problem can be averted. Colossal has teamed up with the University of Melbourne and Research Center TIGRR to resurrect the Tasmanian tiger using preserved specimens. Before the species went extinct, many thylacine embryos and young were preserved in alcohol, like a horrific pickle.In 2018 Dr Andrew Pask, the leader of the thylacine

de-extinction programs, sequenced the thylacine genome from a 108-year-old specimen preserved at the Victoria Museum in Australia. Colossal plans to use gene editing to take the stem cells of a

dasyurid, a family closely related to the Tasmanian tiger, and transform them into thylacine cells.

The cells would create an embryo hybrid, which would then gestate in an artificial womb or a dasyurid surrogate. The animals will then be reintroduced to Tasmania in order to help rebalance the ecosystem. Let's hope the thylacine gets a second chance.

Mountain Pygmy Possum

If you take a trip to Mount Hotham ski resort in Victoria, Australia, and there’s a slim chance that you might come across the Mountain Pygmy Possum. The thumb-sized crumb of cuteness is so rare that for a long time, it was only known by its fossils and categorized as extinct, until it was spotted in a log pile at the ski lodge in 1966.

It spends 7 months of the year hibernating in burrows under snow, occasionally waking to snack on its winter stores. They only fully emerge in the spring to stuff themselves with food and find a mate. Their diet consists of invertebrates, particularly the tasty bogong moth seeds, and berries.Since they made it into this article, you can probably guess that there aren’t many of them left. There are estimated to be fewer than 2,000 left in the wild, in fact. The growth of ski resorts in Australia has destroyed a lot of their environment, disrupting mating practices. Males in particular have been prevented from migrating up the mountain to get the possie. The poor possum has also proved to be a nice meal for invasive species like feral cats and foxes. Due to droughts, there are not many Bogong moths around anymore, either.

If this weren’t enough, climate change means less snow for the possums to burrow in. Without the snowy blanket, their burrow drops down from 96° Fahrenheit to 35° Fahrenheit, freezing them as they hibernate.

The wane in possum numbers is so drastic that Dr Michael Archer of the University of New South Wales decided to step in. Archer didn’t want to risk releasing them back into the mountains, considering said mountains are still being messed up by climate change.But he had a solution. He found that the direct ancestors of the possum lived in lowland forests 15 to 25 million years ago. So, why not try moving some mountain possums there? Archer says they won’t be releasing any possums straight into forests without preparation. Otherwise, "you’d have a very confused possum." The paleontologist says that possums at the breeding Centre are adaptable, eating unusual foods, and mating, and some have forgone hibernation altogether. Archer and his team will trial slowly releasing animals into forests and monitoring the experiment. We’ll have to wait until the possums adapt to woodland living.

Gastric Brooding Frog

The southern gastric brooding frog was discovered in 1972 in Queensland, Australia, and its birthing practices are bizarre. In 1974 herpetologist Mike Tyler discovered how it reproduced, a mother frog begins by swallowing her eggs. To stop those eggs from getting scrambled, her stomach turns into a womb and stops producing hydrochloric acid.

For six weeks after, she would be unable to eat. Meanwhile, twenty to twenty-five tadpoles hatch inside her. As they grow her stomach becomes so bloated there’s no longer room for her lungs, so she begins breathing through her skin. Finally, she vomits out her brood as fully formed froglets.

Alas, the awesome amphibians went

extinct in 1983 when the last frog in captivity died. This was shortly followed by the extinction of the northern gastric brooding frog in 1985. The frogs may have been driven to extinction by deforestation, invasive species such as weeds and feral pigs, and the lethal chytrid fungus, an awful disease that has wiped out more than 90 amphibian species worldwide.Feeling that these animals were too cool to be consigned to the history books, Dr Michael Archer, decided to clone them back to life. He contacted Tyler, who provided the frog’s old tissue samples.The team then put the DNA of the gastric frog into the egg of a barred frog, its closest relative. The problem is that barred frogs only lay eggs once a year. Archer frustratedly admitted, "

We had a few times when we went in and the frogs weren’t laying, and that was that for the year."Unlike other animals up for de-extinction, like the mammoth, the frog was not a social animal and wouldn’t need a complicated surrogate parent. And at 1 to 2 inches in length, the frog was also pretty pint-sized, and could easily be raised in a laboratory. In 2011 Archer successfully produced a frog embryo, and with any luck, there will be mother frogs puking up babies in no time.

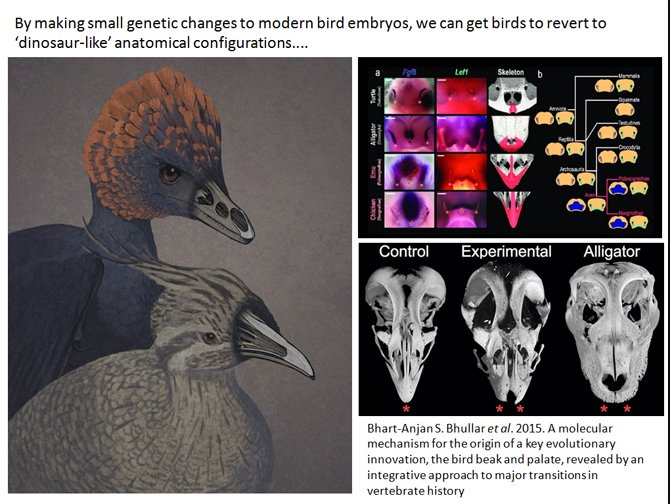

Building A Dinosaur From A Chicken

Did you know that the closest living relative of the terrifying, monstrous, carnivorous tyrannosaurus rex is the humble chicken? What’s more, it might even help us bring the terrible lizard back from extinction.

In 2015 scientists Dr. Bhart Anjan Bhullar and Dr. Arhat Abzhanov reported that they found a way to reverse-engineer the beaks of chicken embryos back into

dinosaur-like snouts. A bird’s beak is formed from praemaxilla; these are two tiny, distinct bone plates at the front of the jaw.In other animals, like ourselves, praemaxilla holds our front teeth in place. As birds evolved their praemaxilla extended and fused together to form a beak. When the bird is an embryo and has yet to grow a recognizable face, a large patch of cells in the middle of what will become its’ face develop proteins. And it is these proteins that form the beak.Bhullar and Abzhanov hypothesized that if they caused a chicken embryo to develop the proteins the way other animals do, the embryo would become a bird without a beak. Instead, they would have skulls like their dinosaur ancestors.

The scientists added microscopic beads into the middle of what would become the chicken embryos’ faces. The beads released chemicals into the tissue that hindered the proteins. Just as predicted, instead of growing beaks the embryos developed rounded, unfused praemaxilla like a dinosaur’s snout. Note that these embryos weren’t hatched, sadly.

Bhullar says, "We were interested in the evolution of the beak, and not in hatching a dino-chicken just for the sake of it." Someone who is interested in dino-chickens for the sake of it is

Dr. Jack Horner, a professor of paleontology at Montana State University.Unlike the nursery rhyme, this Jack Horner is less interested in Christmas pies and more about playing with genetics to create a chickenosaurus. For Horner, four major modifications are needed to make such a creature. The animal would need to have teeth, and a long tail, and its wings would be reverted back into arms and hands.

So what motivates Horner to create a dino-chicken abomination? He claims that "

The most important thing is that you cannot activate an ancestral characteristic unless the animal has ancestors. So if we can do this, it definitely shows that evolution works."

Scimitar Toothed Cat

In 2020 the University of Copenhagen successfully sequenced the genome of Homotherium Latidens or the scimitar-toothed cat, a relative of the Saber-toothed cat. The DNA was extracted from a cat that was discovered in the melting permafrost of Canada’s Yukon Territory.

The specimen lived at least 47,500 years ago; that’s one old cat. Sequencing the cat’s genome allowed scientists to discover more about this apex predator. The felines were certainly a force to be reckoned with. An adult could weigh up to a ton and measure over 10 feet long that’s as big as a polar bear.

They would have snacked on bison, deer, horse, antelope, camel, and even bruisers like the woolly mammoth and mastodon, another distant relation of the elephant. Fossils of the Saber family have been found on five continents, a testament to the success of these deadly creatures.

According to paleontologist Dr Ross Barnett: "

The current geological period is the first time in 40 million years that Earth has lacked Saber-tooth predators. We just missed them." But if these creatures were so formidable what drove them to extinction? Change in climate led to a decline in large mammals, which may have caused more direct competition with other cat species that were better suited to catching smaller prey. When it comes to de-extincting the fearsome fuzzies there are hurdles to overcome. For example, a scimitar-toothed cat has no close modern relatives. They are very distantly related to modern cats, diverging around 22.5 million years ago. In comparison, humans and gibbons only split between 15 and 20 million years ago. In other words, you’d have more luck making some unholy gibbon-human hybrid than getting the two together. The lack of modern relations means that it’s unlikely that these animals will be brought back in the near future.

Woolly Rhinoceros

The Woolly Rhinoceros could reach 6½ feet in height and weighed 3.5 tons, that’s about one and a half times as heavy as modern rhinos, which weigh around 2.3 tons. The shaggy goliaths would while their days away munching on grassland throughout Europe, North Asia, and Asia between 5.3 million and 11,700 years ago. That was, of course, until climate change.

Obviously, not man-made climate change, just the natural warming of the globe that occurred towards the end of the ice age. It could be that their thick fur couldn’t adapt to warming temperatures or that there was a shortage of their favorite food. There’s also a good chance our ancestors had an appetite for rhino meat. In the end, all we know is they died out.

In 2020 a specimen with its organs still intact was found in the melting permafrost of Yakutia in northeastern Russia. Valery Plotnikov, a researcher who examined the remains, told Russian media that the rhino was between three and four years old when it died, most likely by drowning.

As you might’ve guessed, discoveries of specimens in melting permafrost are becoming more common due to climate change. The remains of extinct animals such as mammoths, foals, puppies, cave lion cubs, and a bear have all been discovered in Siberia. Using an 18,500-year-old specimen, the woolly rhino genome was sequenced in 2020.Gene sequencing makes it more likely for the woolly rhino to be cloned by taking its DNA and breeding it with a related, living animal. However, Dr Albert Protopopov from the Yakutian Academy of Sciences in Russia, thinks that the woolly rhino revival is unlikely. Conventional cloning techniques won’t work since there is no modern relative close enough for the rhino to crossbreed with.

Dodo

You may have heard something described as "dead as a dodo" before. Well, put that saying in your back pocket, because it might not be true much longer. The dodo was a flightless bird native to Mauritius, an African island in the Indian Ocean. Scientists believe that Mauritius was formed around 8 million years ago and that dodo ancestors arrived on the island not long after.

The species began to decline when Dutch sailors colonized the island in the 16th century, leading to their extinction 100 years later. Europeans destroyed their habitat and released invasive species, such as cats, dogs, and pigs, which preyed on the bird and their eggs.

The bird’s image has been constructed by incorrect accounts and fanciful illustrations that paint the bird as slow, fat, and unintelligent. In reality, the

dodo was quick and agile, with at least one sailor describing them as hard to catch. The bird may have died out in the 17th century, but that won’t stop scientists from trying to bring them back.

In 2022 Dr Beth Shapiro, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, revealed that a complete dodo genome had been sequenced from a specimen in Copenhagen. Sequencing has revealed that the dodo’s closest relative is the

Nicobar pigeon. If scientists were to bring the dodo back, they would edit the pigeon’s DNA to include dodo DNA.

However, we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves. As Dr Mike Benton, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol, says even if we could do this, the animal would probably not look anything quite like what we would expect a dodo to look like. Another problem is that even if scientists were able to create a pigeon-dodo embryo, they wouldn’t have anywhere to keep it. When cloning a mammal, the embryo can be stuck in a surrogate mother’s uterus and left to grow. Birds have no uterus, so scientists currently have no place to gestate the embryo. Currently, researchers are working on solutions to this problem, but no dodo chicks have hatched yet. Let’s hope they haven’t put all their eggs in one basket!

Pyrenean Ibex

In 2003, something amazing happened and hasn’t been replicated since. For a few minutes, an extinct species was brought back to life. The animal was a bucardo, also known as a Pyrenean ibex. It was a species of wild goat typically found in the Pyrenees Mountains.

Around 220 years ago, the ibex began to die out. Although no one is exactly sure why, it was likely due to, overhunting and their habitat being taken over for farmland. In 1999, there was only one bucardo left; a female called Celia. She was captured by researchers who took a cell and froze it in liquid nitrogen before releasing her back into the wild.Curtains closed on the bucardo species in 2000 when Celia was hit by a falling tree in a tragic ending for an entire species. However, Celia’s story was not over yet. Scientists, led by Jose Folch from the Centre for Agro Nutrition Research and Technology in Aragon, Spain, had the means to clone embryos from her tissue sample.

Scientists emptied the original genetic material of domestic goat ovum and inserted bucardo DNA in its place. These were implanted into other subspecies of Spanish ibex or goat ibex hybrid. A goat became pregnant, and

the experiment worked. Sadly, when the calf was born it had lung abnormalities and died shortly after.Moving DNA from one cell to another can lead to problems during fetus growth and is unfortunately common during cloning. Despite this story’s unhappy ending, this was no doubt a massive achievement and is the only example of an extinct animal being brought back to life, albeit briefly.Some argue, such as reproductive biologist Bill Holt from the Zoological Society of London, that cloning is an unsustainable method of conservation. Even if scientists were successful in de-extincting creatures, the cloned animals’ gene pool would be so small that they’d be prone to ill health and disease. Additionally, with the natural world shrinking, there’s a good chance that a revived species would become extinct all over again.

Black Footed Ferret

The black footed ferret once scurried through burrows underneath the American Plains, and is the only ferret species native to the USA. These days, however, their numbers are restricted to the mountain states. These guys are nocturnal, only waking to hunt prairie dogs. Or, they usually do.

Regrettably, these animals’ habitat is being destroyed to make way for farmland. If that weren’t enough their numbers are dwindling from the rise of the

sylvatic plague. This plague is the same bacterium as the Black Death, which wiped out an estimated 25 million people during the Middle Ages.

The plague is incredibly deadly and 100% lethal to the animals when unvaccinated. Of course, fewer tasty prairie dogs means more hungry ferrets. The black-footed ferret population deteriorated to the point where it was officially declared extinct in the wild in 1979.To save the species from total extinction 18 animals were captured by conservationists for breeding, including one special female called Willa, but we’ll get back to her later. From the 18 only 7 gave birth to kits. Those 7 were released into the wild and eventually grew to over 300.

As a result, the ferret’s gene pool is more of a puddle, with the animals being victims of genetic drift. This is when animals are too closely related to produce healthy offspring. To solve the issue scientists turned to cloning. Willa was a girl from Meeteetse, Wyoming. She never bred in captivity and died in 1999.Knowing that her genetics were unique, clever scientists took her tissue samples to be cryopreserved at the Frozen Zoo, a storage facility in San Diego containing over 10,000 living cell cultures, oocytes, sperm, and embryos for organisms under threat. In December 2020 Biotech Company Revive and Restore successfully created

Elizabeth Ann, a clone made from Willa’s cells.

The company expected Elizabeth Ann to reinvigorate those ferret genes, but she needed an ovariohysterectomy, a surgical removal of the uterus and ovaries; and so won’t be breeding. On the plus side, however, Revive and Restore aim to breed more ferrets from her cells. Looks like they might weasel their way out of extinction after all!If you were amazed at these extinct species that could be resurrected, you might want to read our article about

why scientists are reviving lost species that might save us humans. Thanks for reading!