The Worst Prisons In History

](https://beamazed.b-cdn.net/dfhvoxjgb/image/upload/v1741605040/thumbnail1_FINAL_et7jac.jpg)

March 8, 2025

•20 min read

Let's check out the worst prisons in history!

Nelson Mandela said you can’t truly know a nation until you’ve been inside its jails, and this article will go beyond nations, we’re going back through the centuries. From unimaginably hellish prison pits, to very literal suspended sentences, wave bye-bye to the free world as we step inside the worst prisons in all of history, from ancient times to today.

Mamertine Prison

With the society’s penchant for violence and war, pervasive slavery, and harsh punishments, life as a citizen in Ancient Rome could be pretty grim. But have you ever stopped to imagine just how horrible life as a prison inmate would’ve been under the Roman Empire? Well, get ready to learn the history of Prisons.

Known as the Carcer in Latin, Mamertine Prison was an ancient maximum-security prison that dates back to as early as the 7th century BC. Commissioned by the fourth king of Rome, Ancus Marcius, between 640 and 616 BC, Mamertine largely consisted of a network of dank subterranean dungeons.The lowest of those dungeons was known as the Tullianum which was located within the city’s subterranean sewer system. That truly hellish pit was only accessible via a small manhole in the upper cell floor, through which prisoners of the state were thrown to await their fate. With the only way in and out just above arm’s reach for those thrown into the pit, it’s easy to imagine how torturous it must’ve been.Long-term imprisonment wasn’t a sentence under Roman law, and any kind of incarceration was usually intended to be a temporary measure prior to trials and executions. Even so, some very famous faces reportedly spent time in that hell of a Prison.Legend has it that Jesus’ very own apostles Saint Peter and Paul were both held in Mamertine prior to their crucifixions. And if the thought of waiting in a cramped sewer for your own, very public, un-aliving wasn’t horrible enough, some prisoners, like Jugurtha, King of Numidia, were just left in the Tullianum to waste away completely.Oubliette

Medieval prisoners often faced a myriad of painful punishments, but if you’ll believe it, one of the worst often inflicted no violence at all. Also known as bottle dungeons, oubliettes were narrow shafts with only one escape route, through an out-of-reach trapdoor in its ceiling. Oubliettes the name of which is derived from "oublier", the French word for "forget" were sometimes built within the walls of the upper floors of a castle rather than in dungeons, so that victims could hear life going on without them as they were slowly forgotten and left to expire.

But if the idea of suffering the oubliette alone is too horrible to bear, don’t worry! Sometimes prisoners would find themselves sharing the already cramped space with what was left of previous victims not to mention the rats that nibbled on those remains.Oubliettes have been found in medieval castles all across Europe, but one of the most infamous can be found in Ireland’s Leap Castle. Home to the O’Carroll clan in the 1500s, the castle’s oubliette is said to have once been used to hide valuables. But that cold-blooded clan eventually decided to use the space for an entirely different purpose.When Leap Castle was taken over by the Darby family in 1649, its rumored the new owners made a shocking discovery in the castle’s oubliette. Inside, the Darby’s found the dungeon was fitted with a number of wooden spikes, as well as three cartloads of, previous prisoners who’d been left inside.

Gibbet

While most kinds of imprisonment see inmates locked out of sight from the world, our next prison cell was very much a matter of public interest. Gibbeting was a type of imprisonment in which the condemned was locked in a human-shaped cage before being hung up for public display.

Most of the time those who were gibbetted had already met their end at the hands of the authorities but, shockingly, sometimes live prisoners found themselves in gibbets too. One such story tells the tale of a villainous vagrant who, after committing some atrocious deeds, was sentenced to a live gibbeting in the 1600s at a place called Gibbet Moor in Derbyshire, England.As was customary in live gibbetting's, the vagrant was left to succumb to starvation, dehydration, and exposure to the elements, and legend has it his unearthly screams are still heard by hikers today. Accounts of live gibbetting's like that happening in England are rare and often unsubstantiated.However, there is evidence that live gibbetting's were practiced in the British-colonized Caribbean as late as the 1760s. Gibbets were meant as a sort of warning from the state to keep citizens in check and deter any potential crime, but they were also a source of fascination for the public.

The Clink

With a name that’s thought to come from the sound of the clanging chains worn by its inmates, there aren’t many prisons in history with a reputation quite as notorious or significant as the Clink. Established in the mid-12th century in London, England, The Clink Prison was built by the Bishop of Winchester of the day, Henry of Blois, on the South bank of the River Thames.

At the time, the Bishop of Winchester was second in power only to the king of England and ruled an area of London known as the Liberty of the Clink. That basically meant he could act as judge, jury, and serial imprisoner of those under his jurisdiction who didn’t tow his line.The Clink prison was in operation for 600 years, and what initially began as a small operation controlled by the Bishop of Winchester grew into one of the most infamous prisons of all time. Overcrowding was rife in the iron-barred, cold, stone cells of the Clink, and disease and malnutrition were also regular companions to the unfortunates who found themselves clapped in irons.

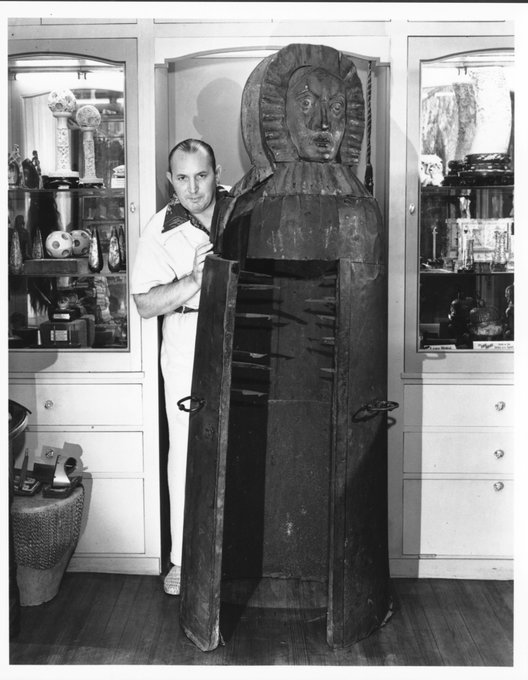

Iron Maiden

One of the most famous torment contraptions of all time, the Iron Maiden’s bone-rattling reputation surely makes it one of the worst one-person prisons cells in history. Often depicted as a human-sized box lined with spikes in the interior, victims of the Iron Maiden would find themselves forced inside with the door shut in on them spikes and all.

Sounds more horrible than you can imagine. Well, turns out that’s kind of the point. While the Iron Maiden is commonly assumed to have been a popular and permanent punishment for criminals of Medieval society, modern historians now question whether they even existed at all.Believe It or Not!, Robert Ripley acquired the Iron Maiden of Nuremberg during one of his travels to Germany. He’s said to have carried the eight-foot-tall device all the way home to join his growing collection of exhibits.

Phu Quoc Prison

Located around 20 miles off the coast of Vietnam, it’s easy to be enchanted by the island of Phu Quoc’s white sandy coastlines and lush plant life. But believe it or not, that tropical paradise was once home to one of the world’s most nightmarish prisons.

El Salvador’s Hell Prisons

It’s clear to see that cramped conditions in prisons have run rampant throughout history, but sadly, the problem of prison overcrowding still exists today. At 12 feet wide and 15 feet tall, those jail cells in El Salvador are often crammed with more than 30 criminals apiece. While those cells were designed to accommodate stays of up to just 72 hours, many prisoners wind up being held in Salvadorian police holding cells for more than a year.

Inside El Salvador's 'hell on Earth' prison where Trump is to banish criminals mirror.co.uk/news/world-new…

Chateau d’If

Originally built on the orders of King Francis I in 1524, the Château d'If was intended to be an island fortress to protect the French city of Marseille from sea-faring attackers. In 1540, however, the island found its new purpose. Thanks to its isolated location and dangerous offshore currents, Château d'If was the perfect escape-proof prison.

The prison was housed inside the original fortress, and prisoners were placed in cells in accordance with their status. The poorest prisoners were kept in the cells on the ground floor, often in horrifically cramped groups of as many as 20 prisoners per cell. The cells had no windows, damp surroundings and only a straw mat or hard floor to sleep on.Vermin constantly scurried underfoot, and indeed the conditions and hygiene were so poor in that part of the fortress that the life-expectancy of inmates inside the prison was just nine months. Wealthier inmates, on the other hand, were able to purchase themselves more spacious cells fitted out with windows and sometimes chimneys. Whatever their social class, many prisoners were sentenced to life imprisonment there, many of whom spent much of their time chained to the walls, or forced into labor.Chateau d’If was a notorious prison in its own right, but it became world famous with the publication of Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo in 1844. It’s the tale of sailor Edmond Dantès who’s wrongly accused of treason and spends 14 years at Château d’If before a daring yet successful escape in a body bag, thrown into the sea.Coffin Prison

While life sentences often make headlines, nowadays, life sentences rarely last the full remainder of the convicted individual’s life. But our next method of historical incarceration was specifically designed to imprison its victims until death do they part.

Immurement, also known as live entombment, was a type of capital punishment in which the victim was permanently enclosed in a tight confined space with absolutely no means of exit. Some of the earliest recorded instances of immurement goes back to priestesses of ancient Rome known as the Vestal Virgins, who used that method to punish those who broke their vows of chastity.Methods of immurement have varied through time, but some of the most common included the victim being locked in a box, or sealed inside a cavity behind a brick wall. Though the history of immurement dates back centuries, shockingly, cases of live entombment are traceable even in more modern times.During the early 20th century, the Urga prison in Mongolia was notorious for its use of what came to be known as coffin prisons. Coffin prisons were extremely small, cramped boxes that resembled coffins that were used as a method of immurement.Usually measuring in at no more than four feet long and two and a half feet wide, those boxes were specially designed to make sure that prisoners trapped inside could neither lie down nor stretch out. Not only were those inside left to contend with intense physical strain and discomfort, but each box had just one small porthole.Guantanamo Bay

Out of all the prisons in history, few are as infamous as Guantanamo Bay. Located within a US naval base in south-east Cuba, Guantanamo Bay has been known for its ultra high security and usage in detaining individuals deemed a security risk by the U.S. government.

Prisoners at Guantanamo Bay often face indefinite detention, meaning many are held without trials or formal charges, nor a clear timeline for release. That uncertainty means that those inside are frequently faced with unimaginable psychological distress and a sense of true hopelessness.Since its establishment as a prison in 2002, the conditions of confinement at Guantanamo Bay have been widely criticized by human rights organizations. Accounts from prisoners have pointed to regular instances of harsh treatment and severe interrogation techniques.Those include sleep deprivation, with guards deliberately making as much noise as possible to keep inmates awake, as well as the opposite: sensory deprivation, where inmates’ eyes and ears are kept covered for days at a time, all while having their hands tied within thick gloves. In protest of their harsh treatment, detainees have been known to go on hunger strikes which are met with even harsher punishments, including the extremely unpleasant practice of force-feeding.Not only does the facility’s remote location further isolate inmates from the outside world, but it also complicates legal and humanitarian access. As Guantanamo Bay is in Cuba, there has been much political debate over whether the facility falls under US law, which creates difficulties for inmates seeking to receive legal help.San Quentin State Prison

Opened in 1854, San Quentin is the oldest prison in California, but sadly, that place hasn’t gotten better with age. San Quentin’s notorious Condemned Row is home to prisoners who have been sentenced to, a government-issued early finale. With a total of 652 condemned prisoners throughout the state, California holds the most Death Row inmates in the entire US, and 546 of them are held at San Quentin.

The condemned prisoners inside are some of the worst criminals in the country and they certainly endure a great deal of punishment for that. The average condemned inmate spends around 22 years living on Death Row, during which they are locked alone inside a solitary cell, often for 23 hours a day.While the more well-behaved inmates are sometimes allowed small luxuries like radios, TVs, and books, those among San Quentin’s 3,200-strong total populace who break the rules can find themselves locked up in what’s known as the Adjustment Center.That Adjustment Center is designed to house inmates who are too dangerous to be elsewhere in the prison, and is locked down so heavily, that even the guards can’t come and go as they please. They get let in at the start of their shift, and the locks stay locked until it’s time to leave all to ensure the state’s most dangerous inmates never escape.