We’ve all imagined what it would be like to visit outer space. But while being an astronaut is a dream for many young kids and adults, there’s one spaceman out there that found himself in a real-life cosmic nightmare, being lost in space! Let's take off on a truly wild tale, traversing through the collapse of nations and into the territory of literal time travel itself, in the story of what happened to Sergeit Krikalev, the astronaut who was lost in space for 311 lonely days!

The Race for Space

Our story begins in the Soviet Union. Russia, specifically. Sergei Krikalev was born on August 27th, 1958, in the city of Leningrad, known as St. Petersburg today. As a young boy, Sergei was all too aware of the intense space race between the Soviet Union and the USA.

An outgrowth of the mid-20th century Cold War, the space race was a series of competitive technological showcases, with each side aiming to prove superiority in spaceflight. As the years went by, Sergei continued to keep his sights set on the stars in his own race for space and gained a degree in mechanical engineering in 1981 from the Leningrad Mechanical Institute.

After graduating, Sergei found work with the NPO Energia, the Russian industrial organization responsible for manned space flight activities for the Soviet Space program. In his early years there, he tested space flight equipment and worked as part of ground-control for space missions. Sergei played a key role among the ground control team during an in-orbit rescue mission of the Salyut 7 space station after it failed in 1985 and was able to remotely guide repairs of the station’s on-board control system.

After these successes, Sergei was selected for cosmonaut training. This intensive course covered a whole manner of space related learning, including astronomy, orbital mechanics, and methods of scientific experimentation.

Upon completing his training, Sergei finally earned his cosmonaut wings in 1986. If you’re wondering why I’m referring to Sergei as a cosmonaut rather than an astronaut, it’s because, technically, cosmonauts are people specifically trained by the Russian Space Agency, and the word literally means ‘universe sailor.’ In early 1988, Sergei began training for his first long-duration space flight aboard the

Mir space station which, at the time, was the largest artificial space satellite in orbit. Launched on February 20th, 1986, the overall objective for Mir was to research how the human body reacted to space travel, as well as observational sciences including studies of the Earth’s surface. On November 26th, 1988, it was finally Sergei’s turn to blast off to Mir on the Soyuz TM-7 expedition, a joint mission involving both French and Soviet space-venturers. The mission came to an end 151 days later on April 27th, 1989.

With a relatively smooth operation under his belt, Sergei found himself desperate to get back up there, to infinity and beyond! But, unbeknownst to Sergei, his next trip would leave him desperate to get back to Earth!

Life on Mirs

By December 1990, Sergei was already preparing for his second space flight as part of the crew for the Soyuz TM-12 mission.

On May 18th, 1991, Sergei arrived at the Baikonur cosmodrome, which was famous for being the world’s first spaceport to launch rockets into space! Alongside him was Anatoly Artsebarksy, an experienced Ukrainian commander, and Helen Sharman, the first British astronaut.

The Baikonur cosmodrome, found in what is now Kazakhstan, had already been the setting for some truly amazing firsts in space travel, including the launch of the first artificial Earth satellite, Sputnik, on October 4th, 1957! It was also the site from which Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to travel into space on April 12th, 1961! While Sergei’s mission was set to be rather routine, as far as flying into space can be, unbeknownst to him, in 311 days, he was going to find himself listed alongside Baikonur’s most historic travelers!If Sergei believed in omens, then he may have clocked early-on that this trip wasn’t set to be an easy one. As the spacecraft carrying him, Anatoly, and Helen approached Mir after a two-day trek to the station, the targeting system failed, meaning that Sergei had to dock their rocket manually.

Space stations like Mir are all equipped with an automatic docking system which enables two spacecrafts to locate each other and stay in the same orbit. Doing this manually is a dangerous affair and just one wrong move can be fatal. But, ever the cool-headed guy, Sergei managed to dock the crew safely.

Mir could accommodate up to six people, but usually just three cosmonauts lived there at once because it was so cramped! The space station saw 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets every day and therefore residents would have to block out portholes to plunge the station into darkness as they slept to simulate night-time. The cosmonauts usually woke up at around 8:00AM on Moscow’s time zone and began work for the day, conducting scientific experiments and maintaining the space station. At 1:00PM the astronauts would ‘come home’ to the communal area for lunch and a workout. But these workouts aren’t just for flexing. In space, it’s really important to keep your strength up as low gravity takes a toll on your muscle mass. The process of losing muscle, also known as

atrophy, has seen astronauts experience up to a 20% loss of muscle mass on spaceflights, and that’s on missions lasting just five to eleven days!

After lunch and that all-important workout, the cosmonauts would spend another three hours working, plus another hour of exercise. The day wrapped up with dinner and some free time in the evening, which most, understandably, spent gazing out of one of the many portholes, marveling at the blue marble we call Earth.While being in space certainly has its wonders, life on Mir wasn’t exactly a glamorous affair. Much like the fictional spaceship, the Millennium Falcon, Mir was often thought of as simultaneously a masterpiece of modern engineering and a complete and utter piece of trash.

Technical malfunctions were pretty much constant on Mir, and by the time Sergei docked for his second visit to the space station, it had developed so many electrical problems that the lights kept flickering off at random intervals.

Not only was this frustrating for the astronauts as they went about their day’s work, but it was also a blinking reminder of just how much they had to rely on this faulty technology to breathe and stay pressurized. In other words, to survive! Each flicker must’ve been horrifying. On top of that, the constant technical mishaps often caused the station’s temperature and humidity to rise and fall rapidly and thus became a breeding ground for microorganisms. As a result, the station reeked of mold, as well as space pilot B.O.!

Basically, Mir was the designated college dorm room of space! But none of that mattered to Sergei, who considered Mir a home away from home! Space was his own personal playground, and he loved the feeling of weightlessness and learning how to fly from one side of the space station to the other. Not only that, but Sergei had an awesome crew around him including his space buddies Anatoly and Helen as well as two other cosmonauts who had been on Mir since December 1990.

On May 26th, 1991, Helen and two of the other cosmonauts completed their missions and headed back to Earth, leaving Sergei and Anatoly to their own mission: maintaining and repairing the station.

A Space of Collapse

Sergei’s mission was planned to end in October 1991, so he still had five whole months left on Mir, and there was plenty of work to do! The most thrilling tasks were the six spacewalks that Sergei and Anatoly had planned to complete during their stay to conduct essential repairs and upgrades to the external parts of the space station.

In the final spacewalk of the mission, terrifyingly, Anatoly’s helmet visor fogged up due to his spacesuit’s heat exchanger running out of water! While still tethered to the station, Sergei had to guide his basically blind commander back to safety and thankfully they made it! However, in August, not far from their mission’s end-date, everything changed. From his intergalactic point of view, Sergei was able to take a whistle-stop tour through the wonders of the world in just an hour and a half as Mir circled Earth, from the pyramids of Giza to the Great Barrier Reef, to the Grand Canyon.

What he couldn’t see were the tanks rolling through Moscow's Red Square, which signaled the collapse of the nation he called home. At the time, the Soviet Union was commanded by President Mikhail Gorbachev who had frustrated communist hard-liners with his reform program,

Perestroika, which sought to restructure the state’s political and economic systems. While tension had been rumbling in the Soviet Union since the 1980s, things finally reached boiling point on August 19th, 1991, when a coup began to remove Gorbachev from power. Despite lasting just a couple days before being called off, the coup had a lasting effect on the USSR, and it was clear that the Soviet Union’s days were numbered.

Given how confusing things were becoming in the USSR, getting accurate news was a challenge, and Sergei worried constantly about his family and friends as they experienced the political unrest on the ground. Sergei kept up with the unfolding events in the USSR as best he could, mainly being kept informed by his wife Yelena who worked in mission control.

©Be Amazed

There were also various amateur radio operators who Sergei was able to speak with via Mir’s communication system. One of these radio operators was American-born Russian language graduate Margaret Iaquinto who

provided him with uncensored news about the political situation in the Soviet Union. Sergei was understandably confused over what was going on, wondering exactly what all this meant for the space program and his mission. Little did he know that he and Mir were about to become entangled in the USSR’s downfall!

The Last Soviet Cosmonaut

As the months unfolded, individual Soviet states began breaking away from the Soviet Union, and by December, most states were independent. One of the last to do this was Kazakhstan, which declared independence on December 16th, 1991.

Kazakhstan's independence threw a sizable spanner in the works for the Soviet space program. The Baikonur Cosmodrome, where Sergei took off from, now belonged to the new government of the republic of Kazakhstan, and they weren’t too keen on sharing. Kazakhstan’s government tried to charge astronomical fees for use of the space complex, and Russia, strapped for money due to the dissolution of the USSR, needed a solution fast! To appease this new Kazakh government, the Soviet Space Program agency, whose headquarters were in Moscow, agreed for a spot on the next shuttle to Mir to be given to a Kazakhstani cosmonaut.

This was a big problem for Sergei, as the inclusion of Toktar Aubakirov, the Kazakh cosmonaut, meant that the planned flight engineer replacement, Aleksander Kaleri, was bumped from the mission. Without the ability to send someone in possession of the skills needed to replace him, mission control informed Sergei that he would have to remain on Mir, indefinitely!

The team of three new cosmonauts joined the Mir crew on October 4th led by Commander Aleksandr Volkov, who Sergei already knew from his first time on Mir. Just six days later, two of the cosmonauts returned to Earth along with Anatoly, whose job as commander was passed over to Aleksander Volkov. By December 26th of that year, the Soviet Union had completely broken apart into 15 different republics, with Gorbachev resigning. The international union that had sent Sergei into space literally didn’t exist anymore, and even worse, the lost cosmonaut was their last priority. His Soviet passport now invalid, Sergei found himself stateless and could only watch helplessly as the nation he’d known on Earth fizzled out. After ringing in both Christmas Day and New Year in outer space, Sergei began to wonder if he’d ever get back down to Earth.

While the company of his fellow cosmonaut Commander Volkov was nice, the problem was that the longer Sergei remained in space, the more strapped for cash Russia became. It got so dire that the rebranded Russian space agency could barely afford to fly food and supplies the 240 miles outside of Earth’s atmosphere to Mir, let alone find the funds to get a replacement for Sergei.

With his future, and even survival, growing increasingly uncertain, Sergei could do nothing but continue waiting and wishing on every passing star that good news would come soon, and that his prolonged stint in space wouldn’t have any dire consequences on his health.

While the effects of long-term space flight are still not fully understood today, even in the 1990s it was known that long-haul space-stayers like Sergei faced some serious health risks. For one thing, being in closer proximity to the sun than on Earth left Sergei exposed to radiation from highly energetic solar particles, vastly increasing the risk of developing cataracts and even cancer. In the face of all this, it should be noted that there was one way for Sergei to get home but using it would incur a heavy toll. There was a Soyuz capsule onboard Mir, specifically designed for returning to Earth in an emergency.

But here’s the problem: Sergei was the only cosmonaut left on Mir with the overall technical know-how to keep things running. If he did decide to leave, it could mean the end of the space station, forever. It seemed that Sergei was caught in his very own spaceman dilemma, what was more important? His mission? Or going home?

Out of the Present

Despite the physical and mental toll that his space stay was taking on him, Sergei’s sheer determination and commitment to his mission outshone even the brightest star! He remained busily working away to keep Mir going for almost three more months.

But Sergei did not spend the rest of his life floating around in space. Help was just around the corner! In March 1992, Germany paid $24 million, in a stroke of political bargaining with Russia, for

Klaus Dietrich Flade to travel to Mir, becoming the first German astronaut in space. This meant that Russia could finally afford a replacement for Sergei, who by this time, had spent a total of 10 months orbiting Earth, having circled the planet around 5,000 times!Elated by the news that he was finally homeward bound, Sergei could finally turn his mind to getting his feet back on solid ground and reuniting with his wife and daughter. Using some of the money paid by Germany, Russia’s space agency selected cosmonaut Aleksandr Kaleri to replace Sergei. On March 17th, 1992, the Soyuz TM-14 crew, including Aleksandr and Klaus, the German whose $24 million travel fare had paid for Sergei’s trip home, launched from the Baikonur cosmodrome towards Mir.

A week after the new crew arrived, Sergei was finally able to make his way back down to Earth alongside Klaus and his buddy Commander Volkov.

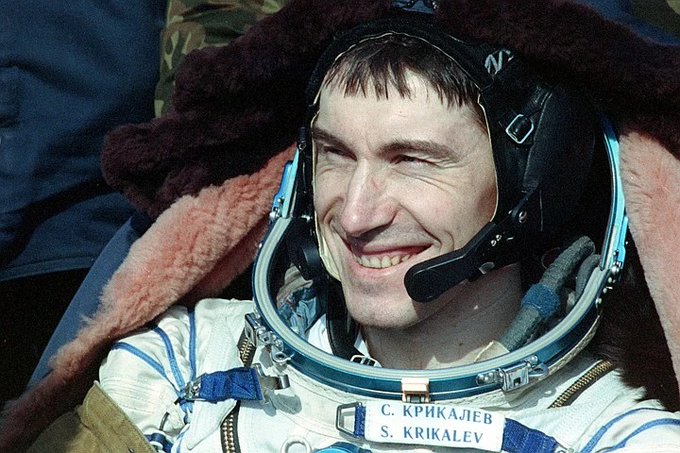

On March 25th, 1992, the Soyuz rocket landed at Baikonur. As the doors opened a small crowd flocked around the landed rocket as a dizzy spaceman as pale as flour emerged. They could just about make out the red Soviet flag on his spacesuit, next to some stitching that read ‘USSR’ in Russian letters, the last true Soviet citizen. After 10 months of muscle atrophy, several men had to help him stand against Earth’s gravity and supported him as he placed his feet on the ground, inhaling breaths of fresh atmospheric air for the first time in 311 days. A fur coat was thrown over him and he was able to enjoy a bowl of broth, his first bit of fresh food in almost a year, on his airplane flight back to Russia, to reunite with his wife Yelena and young daughter Olga.

Arriving in a much-changed Russia, Sergei must have felt like quite the alien! Even his hometown had changed its name while he was up in space from Leningrad to St Petersburg. But the Earth, and the validity of his Soviet passport, weren’t the only things that had changed since Sergei’s time in outer space.We’ve already covered some of the more nefarious physical side effects of space travel, but there’s one side-effect that’d be worth bragging to your friends about: time travelling 0.02 seconds into the future! That’s right: Sergei actually holds the record for the biggest human leap in time travel!

How’s that possible? Well, according to

Einstein’s theories of relativity, the speed at which an object is traveling, and the distance from a massive gravitational source, like the Earth, can actually change the way that object experiences time! Sounds kinda wooey, doesn’t it? That’s what the practically-minded manufacturers of some of the first GPS satellites thought, too. Yet, when they sent their satellites up, which featured atomic clocks accurate to the nanosecond, they were astounded by what they found. Within minutes of activation, compared to the clocks they had on Earth, the internal clocks of the satellites were running very slightly faster, but by enough of a factor to render the GPS readings useless.

Within hours, the GPS readings were inaccurate by tens of miles! They had inadvertently proven Einstein’s theories right. But what exactly are those theories? Einstein’s theory of special relativity states that an object moving faster relative to another will experience time slower. The theory of general relativity, meanwhile, tells us that time runs faster for an object the further it is from a source of gravity. These two principles, working together in space seemingly at opposites, don’t quite cancel out, and general relativity tends to win, as far as things orbiting the Earth are concerned.

This means objects orbiting Earth, Sergei Krikalev included, experience time as moving faster than those on Earth. This meant that, upon his return, Sergei was technically 0.02 seconds older than he would’ve been had he remained on Earth. It also means that all GPS satellites require compensation systems to account for the effects of time dilation in order to function! And you thought an astronaut being stuck in space was going to be the weirdest thing you learned today!

Reach For the Stars

You might think that 311 days' time-traveling in space would be enough for a lifetime, but Sergei wasn’t finished. He continued his celestial career as a cosmonaut and was back above the sky just under two years after returning home.

In fact, Sergei took part in a further four missions between 1994 and 2005 and made space history books again on November 2nd, 2000, when he was a part of the crew who embarked on the first long-duration expedition to the International Space Station!

Overall, through his space-faring career, Sergei logged a whopping 803 days, 9 hours, and 39 minutes in space, spanning across 17 years. In 2005, he capped off his spaceflight days as the commander for the 11th expedition to the

International Space Station.Sergei later reflected on his time in space, claiming that everyone who has been up there gains a global perspective, and issues revolving around differences between nations begin to seem absurd. After all, from space, we’re all just tiny, relatively insignificant beings on our pale blue dot, nestled among the stars. With the vast, expansive nature of the universe being enough to make your head spin, there’s only one thing for sure: Sergei’s story is truly out of this world!

](https://beamazed.b-cdn.net/dfhvoxjgb/image/upload/v1716777901/genius-ideas-that-should-exist-everywhere-part-4/5v95m4coqagBP9aP4lktIH.jpg?width=400)