Every city in the world has its own identity. But aside from the people living there, one of the main deciding factors of a city’s identity is its appearance. When we think of New York City, we picture skyscrapers and Lady Liberty; with London, it’s Big Ben and the London Eye; for Sydney, it’s the Opera House. But the cities we know and love could have looked very different, if some of these weird, incredible and just plain crazy proposals had been built. From airports built over rivers to gigantic hyper-buildings, we’re going to explore what major cities in the world could have looked like, if Earth’s most ambitious architects had their way.

London, England

London has been one of the world’s most significant cultural centers for centuries. But this city, defined by its array of landmarks from the Houses of Parliament to Tower Bridge, could have looked considerably different if some of these unusual designs had been brought to life.

Can you imagine heading into a London souvenir store and seeing, in amongst the little red phone boxes and royal wedding keychains, a model of the river Thames with an airport built over it? I know, pretty ridiculous, but

this was an actual plan, proposed in 1934 and featured in Popular Science Monthly. This bizarre design would have been located right next door to the Houses of Parliament, between the Lambeth and Westminster bridges. The initial intention was to facilitate easy national and international business travel for those based in the area. Sufficiently elevated to allow the tallest masts of passing ships underneath, the Westminster City Airport would feature an enormous flight deck, from which single-propeller aircraft could launch, and areas for re-fueling and plane storage directly under the main deck. The colossal pillars that lifted the platform out of the Thames would contain elevators to allow travelers to journey to and from the deck. In a fantastic CGI reimagining, developer Barratt Homes even

added a classy boarding suite for the most refined customers at the base.

Some of London’s existing tourist-traps came close to looking totally different, too. The Royal Courts of Justice, undeniably grandiose in their current designs, could have taken the whole ‘assertion of power and authority’ thing to whole new levels, if Alfred Waterhouse had won the 1867 competition deciding their design. Waterhouse’s design featured an imposing central tower, which would have been taller than the city’s other buildings at the time; a constant reminder to criminals that they were being watched.

But don’t feel bad for Waterhouse, despite his lack of a win here, he was later commissioned to design the Natural History Museum, which sports some of those gigantic towers he loves so much. The famous Trafalgar Square may have also looked very different, if Sir Frederick William Trench had anything to do with it. Trench proposed that, instead of the monolithic Nelson’s Column that stands there now, a 300-foot pyramid should be constructed in the square. Trench’s argument was that they could commemorate the 22 years of the Anglo-French wars with this 22-step giant, but apparently Egyptmania hadn’t quite swept the British public in the 1820s, as his plan was largely ignored.

Arguably, the most bizarre of London’s architectural near-misses was Watkin’s Tower, a highly ambitious project with eyes to the sky. An effort to overshadow the Eiffel Tower as a standpoint of modernity, Watkin’s Tower was planned to stand well over 1,000 feet tall.

The railway magnate behind the build, Sir Edward Watkin, had actually tried to hire Gustave Eiffel himself to design the tower, but Gustave declined out of fear of being perceived as a traitor to his country. Regardless, construction of the beast began in 1893, and the tower would feature restaurants, theaters, Turkish baths, a hotel and even a sanitorium, all of which would be illuminated by cutting-edge electric lighting. But the Tower’s nickname soon shifted from the Great Tower of London, to

Watkin’s Folly. Financial issues halted the project in its early stages, and the tower’s base received a dynamite demolition in 1907.

Paris, France

Towers and bridges are one thing but re-designing a whole Parisian district is something else entirely. French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, however, chose to think big with his ‘Ville Contemporaine’. Designed in 1922, Le Corbusier’s utopian, urban plan was a reaction to a city he found far too congested, with its streets unable to meet the demands of the growing populace who called Paris their home.

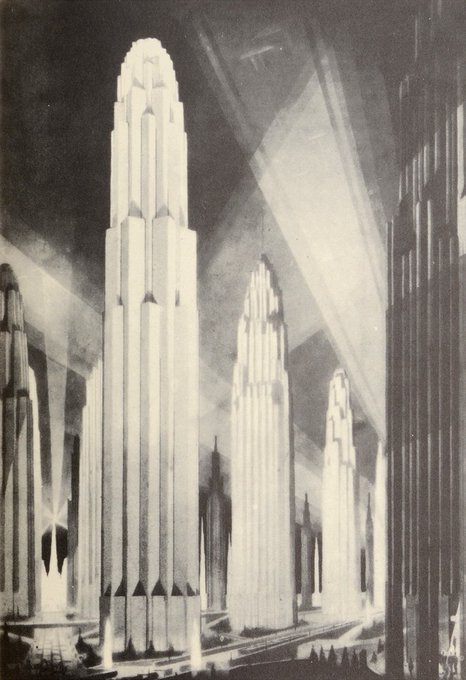

In Le Corbusier’s vision, which was oddly-predictive of the domineering spaces that would later be found in Soviet Russia, only a little greener, he hoped to house three million inhabitants in 24 steel-frame, 60-story skyscrapers. These giants of gleaming glass would line the main avenue, which was sub-divided for three purposes: an underground tunnel for the heavy traffic, a ground-level boulevard for lighter vehicles, and arterial roads for the fastest of travelers.

Surrounded by flourishing canopies of trees and plenty of open, green space, Le Corbusier envisioned the whole city as a park, where the eye was constantly stimulated with the impressive mingling of flawless architecture and light-drenched, natural beauty. Unfortunately for him, when Le Corbusier presented his ideas at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1922, he received a lukewarm reception, and the renovated city remained nothing but a utopian pipedream.

Sydney, Australia

Sydney is known for its distinctive Opera House and is a city rich with culture and identity. But we can’t help wondering whether some of these proposed designs would have stuck Sydney more firmly in the minds of people around the world as a place of weird and wonderful architecture.

In 1922, Sydney’s government launched a competition to design a bridge between the northern and southern shores of the city. This bridge would inevitably become a distinctive feature of the city, and a flood of entries were submitted, including an intriguing design by one Ernest Stowe.

Stowe’s design featured a cathedral-like tower, a central point at which roads from the three surrounding shores could meet. Though the design was 400-feet longer than the competition’s specifications requested, Stowe’s design was only rejected by a narrow majority.

If government buildings reflect a city’s attitudes towards authority, then Sydney must be pretty laid back. Despite the impressive architecture found elsewhere in the city, Sydney’s Parliament House is subdued, to say the least. But the city’s 19th century inhabitants originally had something much grander in mind. In 1861, Irish architect William H. Lynne won a competition to design the new Parliament House. His design was a Gothic imagining that didn’t hold back, featuring grandiose spires, ornamental archways and a large central tower.

Unfortunately, due to lack of funding for a complete renovation on this scale, Lynne’s design never came to fruition, but it certainly would have created a very different effect, standing where the current building does now.Sydney’s most iconic landmark, its Opera House, very nearly had a totally different appearance. In a contest deciding the Sydney Opera House’s design,

architect Joseph Marzella’s entry was runner-up. Taking a more conventional approach than the winner, Jørn Utzon, Marzella imagined the Opera House composed of a circular plan, with ascending spiral stairways, sheer vertical lines, and what resembles an XXL toilet roll on top.

Sorry Marzella, but there’s a reason your design has been compared to a vacuum cleaner part; the building would have resembled more of a factory than the astounding work of ingenuity we see today, and it would likely have struggled to put Sydney on the map in such a significant way.

Moscow, Russia

Although a great deal of Stalinist architecture survives in Russia from the Soviet era, like the thousands of uniform tower-blocks found in many Russian cities, nothing serves as quite the reminder of Russia’s troubled past as the planned Palace of Soviets would have.

Designed in 1933 as a testament to Soviet dominance, this highly-elaborate fusion of neoclassical style and modern skyscraper would have been the largest structure in the world, of its day, had it been completed. Construction of the Palace, which would have featured a titanic, 300-foot tall statue of Lenin, began in Moscow in 1937, building directly on top of the newly-demolished Cathedral of Christ the Savior. The tower, over 1000-feet tall altogether, was designed by Boris Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Gelfreikh. However, the German invasion in 1941 halted its construction, and it was disassembled, its parts scattered across Russia for use in construction for the war effort. This enormous structure would be visible from all over Moscow, and had the Soviet Union not disbanded, would serve as an aggressive reminder of who was in charge. But with history’s occasional sense of humor, the ground upon which it was once begun now houses one of the world’s largest open-air swimming pools.

Berlin, Germany

Anyone with a basic knowledge of history can tell you that the Nazi party in Germany between World Wars 1 and 2 were obsessed with power, control and lavish authoritarian displays. They had some cruel, crazy ways of achieving this control, but it doesn’t get much crazier than Adolf Hitler’s plans to re-design the entire city of Berlin.

With aims to entirely renew the city under a new name,

Germania, the plans for the new city represented Hitler’s goals for the entirety of Germany, had they won the Second World War. Through the center of the city, there would be a four-mile avenue, named the ‘Boulevard of Splendors’.

Colossal landmarks lining the Boulevard would serve as a constant reminder that non-conformity was not tolerated. Roads would be purely reserved for cars, with pedestrians being forced into underground tunnels to navigate the main boulevard. An enormous arch big enough to fit the Arc de Triomphe in its opening would sit at the southern end of the Boulevard of Splendors, an expression of superiority to Germany’s European neighbors. The greatest feat of all would have been the Volkshalle, or the Great Hall, which was designed in the early 1930s by architect Albert Speer and was inspired by the Roman pantheon. At 950 feet tall, the building would have been big enough to hold 180,000 people; providing the ultimate environment for Hitler to deliver his rousing nationalist speeches.

Hints of the central boulevard’s construction can be seen in Berlin today, but the re-development of the city ground to a halt as World War 2 escalated. The Great Dome itself never saw the light of day, save for a huge concrete block designed to test the ground’s ability to hold the weight of the Volkshalle, but if it had been constructed there’d be no escaping the Nazis’ clear message of dominance and aggression.

New York City, USA

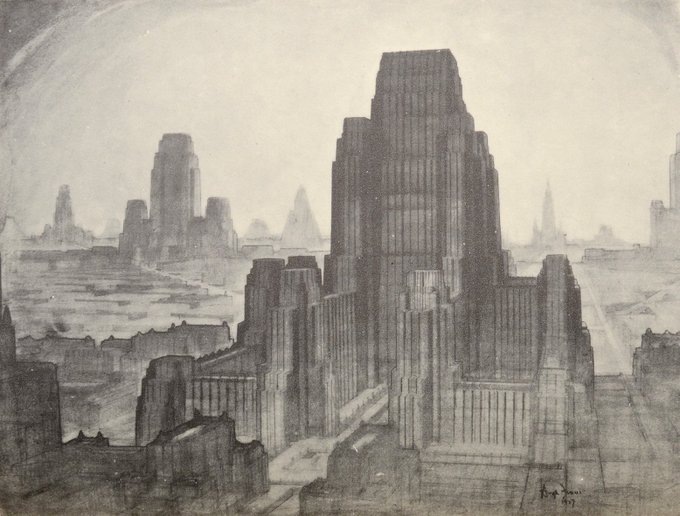

Perhaps the pinnacle of iconic cities on Earth, New York City’s distinctive skyline, powerful Hudson river and Statue of Liberty have constantly captured the world’s imagination through cinema and television for the past century. But the classic cityscape we’re familiar with would have had some very different iconic features if these planned developments had gone through.

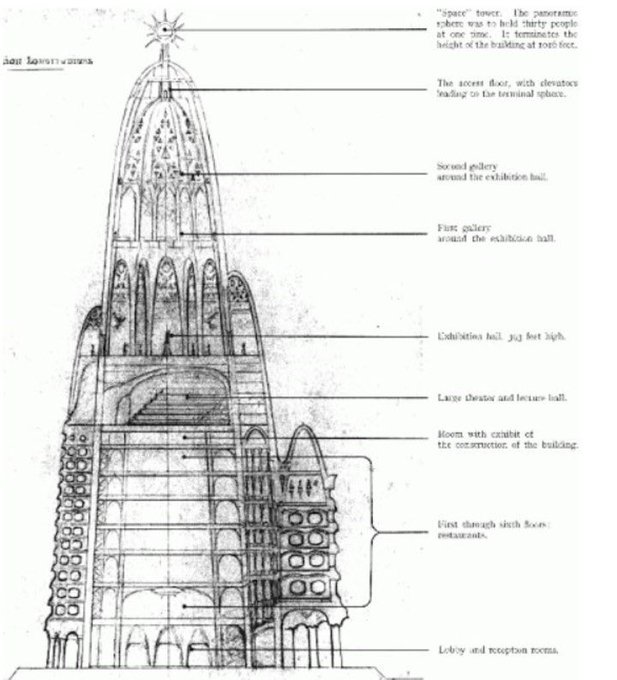

The most obvious differences would have come from a sprinkling of strange skyscrapers in Manhattan. The first of these, commissioned in May 1908 but never constructed, would have been called the

Hotel Attraction. This tower, resembling London’s gherkin on steroids, was designed by Spanish architect Antoni Gaudi, and drew inspiration from the unfinished Church of La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona.

Though the planned height of 1,250 feet wasn’t entirely viable at the time, it would have stood out in Manhattan, its curves contrasting against the straight lines of the other skyscrapers that have since been built in the area. The Hotel’s design recently received media attention as an entry into the World Trade Center memorial design competition, and interestingly enough, Ground Zero sits upon the exact spot the Hotel Attraction would have been built. Elsewhere,

Grand Central Terminal, one of New York’s most famous locations, has experienced many intriguing re-design proposals over the years. In the 1903 contest to decide its original appearance, architectural firm McKim, Mead and White put forward a grand design, featuring a 60-story clock tower reminiscent of a Catalan church campanile.

Though the tower was not a feature of the winning entry, it’s fun to imagine New York’s very own Big Ben chiming above the busy commuters. When Grand Central was constructed in 1913, the architects behind it had envisioned the eventual construction of a skyscraper above it. This came to fruition eventually and can be seen today with the Met Life building, but one proposed design was very different. Resembling a gigantic bundle of sticks,

I. M. Pei’s futuristic tower, named the Hyperboloid, would have reached 80-stories high if it had been pursued after its design in the 1950s. The criss-cross of structural supports would have provided stability as well as a distinctive look, allowing for open-plan flooring throughout the building, but stakeholders ultimately opted for a cheaper, less inventive choice.

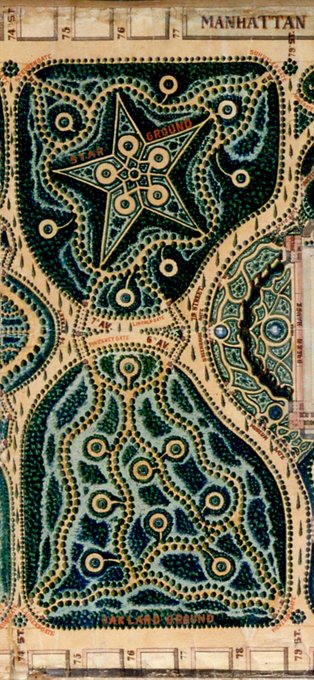

Jumping down from the high ground now, New York City’s Central Park was not always intended to be the organic-looking assemblage of open spaces we see today.

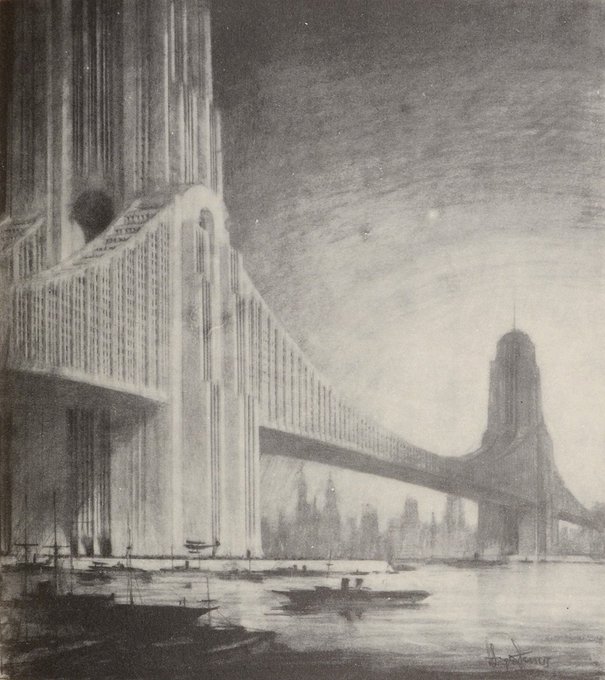

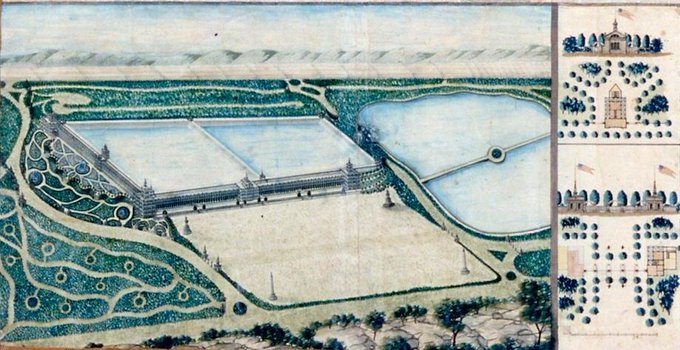

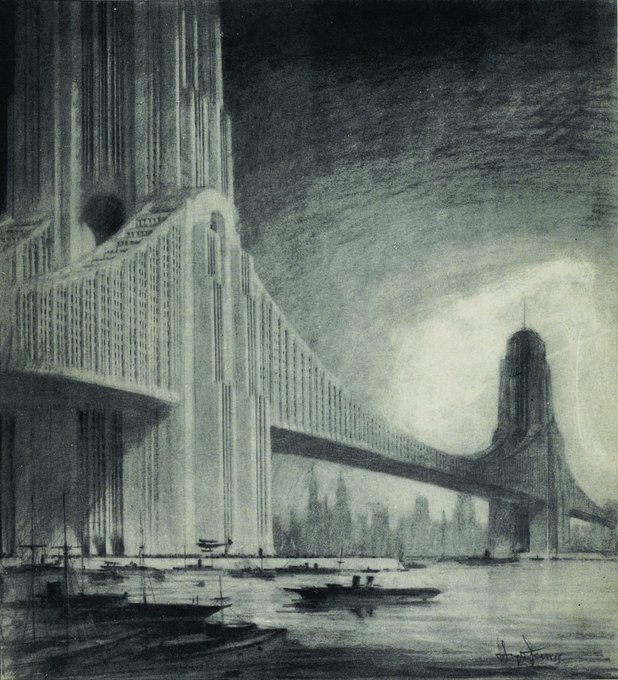

One of 33 entries in the 1857 competition deciding the design of the park, engineer John Rink imagined a very neat, symmetrical park with winding paths and immaculate topiary. Inspired by the gardens of Versailles as well as European fairy-tales, Rink’s plan called for waterfalls, botanical gardens and large, mirrored pools, but was decidedly too un-American for the judges. Let’s dive into the Hudson river now, where things are about to get very strange. In 1925, architect Raymond Hood asked the question: if we can build massive skyscrapers and enormous bridges, why not bring the two together? Hood proposed constructing a series of

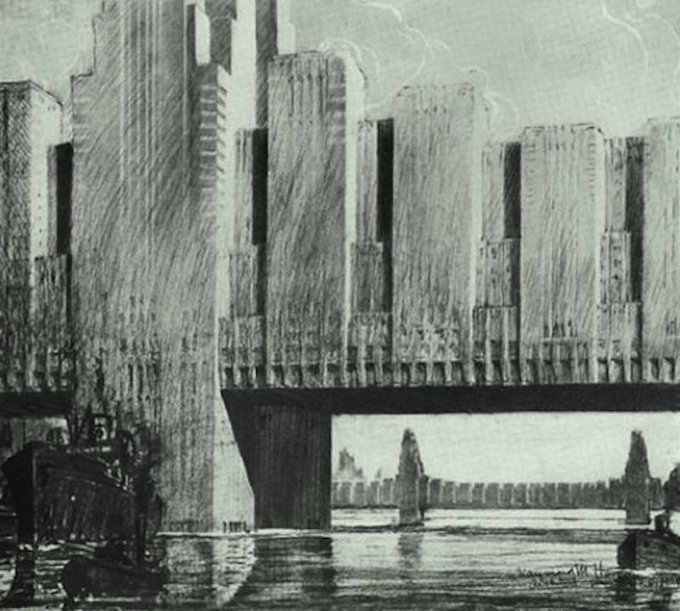

apartment bridges, which would feature rows of skyscrapers, each building capable of housing 50,000 people. Hood even suggested developing these bridges into towns of their own, complete with schools, churches and theaters.

But whacky plans for aquatic expansion don’t stop there. In a design that would have totally changed the appearance and flow of the city, William Zeckendorf proposed building a

$3 billion airport, smack dab in midtown-Manhattan. The 990-acre project would have stretched 144 blocks, all the way from 24th to 71st street, 200 feet above street level. Not only would aeroplanes be able to land and take off from its runway on the roof, but it would have also had piers and internal docks for ships to anchor.

Complete with restaurants, offices and waiting rooms, the aim was to reduce the need for Manhattan residents to trek elsewhere for air travel; providing a close-by and convenient place to fly up, up and away. Unfortunately for Zeckendorf, New York’s commissioner Robert Moses dismissed the plans as ridiculous, and they never came to be. I hope you were amazed at what major cities in the world could have looked like. Thanks for reading!