In 2020, a global pandemic has claimed lives and crippled economies, while wildfires have ravaged the landscape in various locations. Political and social chaos has consumed nations, and floods, earthquakes, explosions, and oil spills have caused destruction the world over. But as bad as 2020 might have seemed, it ain’t got nothing on the year 536. So, strap in, and let’s rewind the clock almost 1,500 years, to a truly hellish year where summer never came.

The Worst Year To Be Alive

What would you do if you woke up one morning, pulled back the curtains, and despite it being daytime in the middle of summer, the sky was dark? Not only that, but the usual warmth of summer has been replaced by bitter cold. And what if this coldness had caused much of the year’s harvests to fail completely, leaving people starving to death in the streets? On top of that, a deep fog is gathering everywhere you look, and rumors are stirring of a horrendous, highly-infectious sickness killing people without mercy.

Depending on what kind of person you are, you might think the end times had come. That’s what many people living in the year 536 of the common era, otherwise known as 536 A.D., concluded when they observed those exact things. The inexplicable darkness, and the famine and pestilence that soon followed, were seen as omens that the gods had turned their back on humanity for good.

One ancient chronicler writing about these dark days shared the anecdote of a plague-stricken Egyptian city, where a crying child was told to, “Go now, and weep not, for this punishment is the payment for heresy and sin." This morbid, apocalyptic feeling could be found all over the world at this time, and it all seemed to stem from that mysterious, darkened sky. So, just how dark was it?Well, when the

Byzantine historian Procopius wrote of the sun giving “forth its light without brightness” for the entire year of 536, he wasn’t just being dramatic. Countless other sources from the time back his claims up, like Cassiodorus, a Roman politician, who wrote of citizens being disturbed by how, even in daytime, their bodies were casting no shadows. He also noted that the seasons appeared to be jumbled together into one long winter. Others described the sun as being in an 18-month-long solar-eclipse-like state, noting that only 3 hours of substantial daylight would occur each day. There was clearly something very wrong, but what had caused this darkening of the heavens?

Volcanic Winter Of 536 AD

For many years, this question left modern historians scratching their heads. That was, until 2018, when researchers at the University of Maine discovered a culprit. Analyzing ice from a Swiss glacier, the researchers found unmistakable evidence of a cataclysmic volcanic eruption occurring in 536 A.D, demonstrated by the presence of volcanic glass particles within the layers of ice.

Further analysis suggested the eruption occurred in Iceland, though some geoscientists believe it may have occurred in Central America instead. Wherever it occurred, the eruption spewed ash across the Northern hemisphere in such quantities that, for around a year and a half, the sun’s light could barely penetrate through. The 2018 glacier analysis discovery was found to line up nicely with separate observations made more than two decades earlier, revealing the shocking extent of the eruption’s impact. In the 1990s, scientists studying tree ring cross-sections determined that summers around the year 536 were unusually cold, as evidenced by abnormally-small amounts of growth in the rings corresponding to that period. As it turned out, after 536, the world saw its coldest decade on record in 2,000 years. And thanks to the glacier analysis, we now know this big chill was directly connected to the same thing that had cast an apocalyptic darkness over the world of 536: A massive volcanic eruption.

Of course, back in 536, very few people were aware the eruption had even happened, let alone the fact that it was responsible for the global darkness and dropping temperatures. But with the benefit of scientific understanding, we’re able to tell precisely how this powerful eruption caused a cooling darkness to spread across the land. Part of it came from fine ash particles, which rode atmospheric currents in enormous quantities and collectively cast a foggy shadow onto the Earth below. This is because, when volcanoes erupt, sulphur dioxide is released in great quantities into the atmosphere, where it combines with water to form sulphuric acid aerosols.

These tiny droplets of sulphuric acid reflect some of the incoming radiation from the sun, preventing it from reaching the earth and warming it. These aerosols would’ve taken years to settle out of the atmosphere, extending the cold spell far beyond the period of darkness witnessed in 536.With the influence of the Earth’s main energy source severely hampered by the veil of dust and gas, global summer temperatures dropped by between 2.7°F and 4.5°F, with disastrous consequences. Without the necessary energy, crops failed to grow in regions ranging from Ireland, to Scandinavia, Mesopotamia, and even China. One ancient Syrian scribe wrote how, during that year, “fruit did not reach the point of maturity, and all the land became as though transformed into something half alive, or like someone suffering from a long illness.”

And while the ever-present, foreboding ash-fog that afflicted the Middle East, China and Europe was certainly eerie, the effects went far beyond giving people the heebie-jeebies. In areas of China that were accustomed to sunny summers, the heat-blocking veil that lay heavy in the skies led, instead, to summertime snowfall. This delayed the year’s harvest, leading to devastating famines nationwide. The same effect was experienced in Ireland, where various sources recorded failures of the crops needed for bread not just in 536, but also in the 3 years that followed. At the same time,

Teotihuacán, a large city in Mesoamerica, felt the effects arguably harder than anywhere else. It’s theorized that famines and droughts resulting from the eruption’s catastrophic climate effects were bad enough to lead to the society’s collapse. Evidence suggests the poorer citizens of Teotihuacán, unable to feed themselves, turned on their ruling class, sacking and burning their homes, presumably after stealing any food that was being hoarded. In the wake of all this chaos, the Mesoamerican city was brought to its knees, leaving it vulnerable to attacks and exploitation by neighboring cities, leading to its permanent demise.

With famine rampant across the world, the events of 536 would not be quickly forgotten. But neither could they be explained by people at the time, leading many to assume these difficult events were the work of the gods. Historians have suggested we can trace the impact of this year by the efforts people appear to have made to bring back the sun. The dust-veiled sky, dimming the celestial bodies above, seems to have been perceived as an omen of doom for Scandinavian communities in particular. Various hoards of gold, jewelry, and other precious items have been discovered in Scandinavia, seemingly deposited around this time. It’s possible that these were left in an attempt to bring the sun back, and with the hoards being of substantial size, it’s clear they weren’t messing around.

With darkness, starvation, and death ever-present for the duration of this period, archaeologist Morten Axboe has suggested that the year 536 may even have influenced the

later formation of important Viking myths. Norse mythology describes something called Fimbulwinter, meaning great winter, where three consecutive winters occur without any summer in between. In the myths, the Fimbulwinter is immediately followed by Ragnarök, where a great battle of the gods sees much of the world destroyed and eventually reborn anew. Considering these mythological traditions don’t appear to have existed before the 6th century, Axboe suggests that the long-lasting memory of the events of 536 A.D. may have inspired their creation. So, while it was certainly a terrible year, the one positive is that, without its events, we may never have been able to watch Thor: Ragnarök today!With a year bad enough to seemingly inspire apocalyptic legends, it’s fair to argue that 536 was one of the worst 365 days in human history. It certainly eclipses some of the exaggerated claims made by drama queens online that 2020 is the worst year ever. But, as crazy as it sounds, 536 A.D. was just the beginning.

First Plague Pandemic

A large part of the reason 536 is considered to be the worst year in human history is because the suffering it produced left humans worldwide particularly vulnerable to what came next. The period that followed continued on a serious downturn for humanity, with more chilly summers brought about by two additional volcanic eruptions thought to have occurred in 540 and 547, respectively. But the period immediately following 536 A.D. is most vividly remembered for something that ravaged the emaciated communities and vulnerable immune systems of the starving: the first plague pandemic.

This occurred long before the Black Death of 1347-1351, which you’re probably more familiar with. This earlier plague was first reported in Egypt in 541, with an outbreak of the disease caused by Yersinia pestis, a bacteria transmitted to humans by the Oriental rat flea. Those infected with the disease experienced agonizing buboes as their lymph nodes became swollen, often to the point of bursting. Alongside these, the infected experienced high fever, coughing, seizures, gangrene, and the painful rotting of flesh, among other horrendous symptoms that culminated in death in upwards of 2/3rds of cases. With the failed harvests that began in 536, many European countries saw migrations of starving folks looking for better climates to grow crops. All the while, various wars were being fought, many involving the Eastern Roman Empire under

Justinian the 1st, who was trying to expand and maintain Roman influence around the world. These wars and migrations meant that, when the plague broke out, it was allowed to spread even quicker than it might’ve otherwise. This was thanks to the flea-carrying rats that inevitably snuck into the food reserves on the carts and ships these mass movements of people took with them.

But the mass-migration of starving people wasn’t the only way the events of 536 had accelerated the later spreading of the plague. Research carried out in recent years has found that, when a flea is infected with Yersinia pestis, the bacteria can cause a blockage in the flea’s gut. This blockage prevents the flea from being able to properly digest the blood it feeds on, leaving it in a perpetual state of hunger.

These blockages in the fleas’ guts are considerably more likely to form at lower temperatures, as they tend to disintegrate as temperatures approach the mid-80s°F, or 30°C. With the volcanic eruption of 536 lowering global temperatures, particularly in summer, the plague-carrying fleas, whose guts were consequently more likely to become clogged by the bacteria, became ravenous. Desperately seeking a filling meal, but to no avail, they would be increasingly likely to seek alternative sources of blood. This, in turn, may have led them to hop from rat-to-rat, and eventually, to human hosts, as their insatiable hunger took hold. By feeding on humans more regularly, the fleas were inadvertently accelerating the transmission of the plague.This accelerated outbreak proved particularly devastating in places like the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, Constantinople, known now as Istanbul in modern-day Turkey. A historian of the time by the name of Procopius recorded that, at its peak, the plague was claiming 10,000 lives a day in Constantinople. While some modern historians dispute the accuracy of this figure, the devastation was undeniable. Even the ruler of the Eastern Roman empire at the time, Justinian the 1st, contracted the disease, though he was one of the lucky few who managed to survive.

Outbreaks of the first plague would continually reoccur after this initial pandemic without any real respite for over 200 years. While the precise figures are heavily disputed by historians, as many as 100 million people may have died by the time these recurrent outbreaks finally slowed down.

While deadly plagues certainly created some of history’s worst years, it was 536 A.D.’s climate-cataclysm-causing volcanic eruption that really made it stand out. But 536 wasn’t the only year in history where summer never came. Another of these years occurred in 1815.

The Tambora Explosion & The Volcanic Winter

On the 10th of April that year, Mount Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa exploded in one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in recorded history. The plume of the eruption reached 141,000 ft into the sky, and as many as 10,000 people died in the immediate blast. Some of these unfortunate souls were scorched and choked to death by the superheated ash, while others were crushed by falling debris.

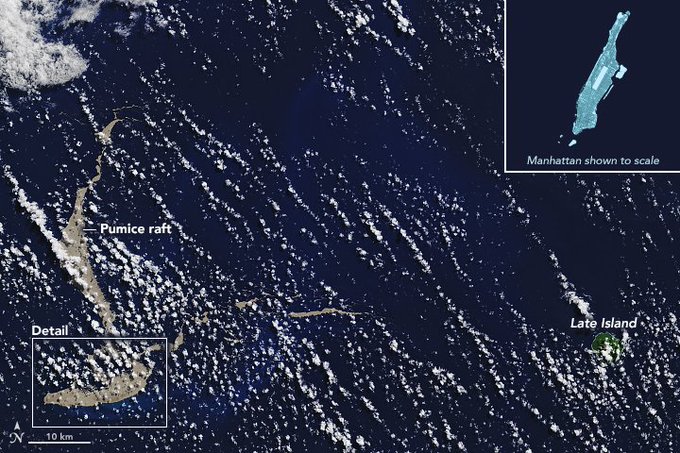

Huge amounts of vegetation on the island was destroyed in the blast, while volcanic rock blanketed the surrounding ocean in

floating patches like these, measuring up to 3 miles across. The eruption triggered a moderately-sized Tsunami, which struck the shores of various other islands in the Indonesian archipelago, taking an estimated 4,600 islanders to a watery grave. Altogether, an estimated 100,000 people on Sumbawa, Bali, and other nearby islands died from the direct and indirect effects of the eruption. But the eruption’s broader impacts reached all the way around the northern hemisphere, as atmospheric ash and gas caused average global temperatures to drop by 0.7–1 °F. Much like in 536, failed harvests were reported in the United States, India, China, Europe, the U.K., and Ireland, to name but a few.

The effects were so severe in Europe that riots and looting broke out in several cities, as citizens faced what’s considered the worst famine of the 19th century. Through this period, a haze was noted across the world, dimming the sun’s rays and causing vibrant yellow and red sunsets. We now know these colorful sunsets were caused by the presence of volcanic ash and gases in the atmosphere, which caused scattering of sunlight. This scattering resulted in the appearance of vivid colors, as certain other wavelengths were filtered out. These hazy, golden views were captured by various artists at the time, and these paintings were among the few good things to come out of that disastrous eruption.

Another unexpectedly positive outcome was Mary Shelley’s now-world-famous novel, Frankenstein. The cold, gloomy weather triggered by the 1815 eruption forced Shelley and her friends to remain indoors during a vacation at Lake Geneva the following summer. During this indoor retreat, inspired by the gloominess, they entertained themselves with a ghost-story competition, and Shelley’s Frankenstein was created as a result! Similar to how 536’s sun-blocking eruption may well have led to the creation of the Ragnarök myth, it goes to show that dark times, if nothing else, can make for some great stories.The similarities between the years 1815 and 536 are easy to notice, but there’s another coincidental similarity that seems to justify superstitions surrounding years without summer. Just as 536’s blackened skies were soon followed by a pandemic; so were those of 1815.

Just over a year after 1815’s summer that never came, a devastating

cholera pandemic emerged that didn’t subside until 1824. The outbreak spread throughout South and Southeast Asia, stretching to the Middle East, eastern Africa and even the Mediterranean Coast. The bacterial infection of the small intestine left its victims with near-constant, watery diarrhea and vomiting, leading to extreme dehydration, and ultimately, death, if untreated. This particular cholera strain emerged in India, after consecutive droughts and flooding, indirectly worsened by Tambora’s eruption, triggered mutations in the cholera bacteria, making it particularly deadly.

While this cholera pandemic didn’t reach as far as Europe, it still claimed between 1 and 2 million lives in India alone. That’s more than enough fatalities for those inclined toward superstition to grow a little uneasy about what might be on the horizon the next time a volcanic eruption blocks out the sun.

A Volcano Could Shut Down The World

In 2020, we seem to have skipped the major volcanic eruption and gone straight to the pandemic. But what if we did see an eruption capable of blocking out the sun, like the one that occurred in 536? It would certainly mean the end for anyone living in the immediate area around wherever the eruption took place.

Just like in 1815’s eruption of Mount Tambora, pyroclastic flows, choking ash and possibly even tsunamis would wipe out settlements along vast stretches of land. A serious eruption at the volcanic Mount Rainier in Washington, for example, could see Seattle devastated by ash and mudslides. Similarly, the Italian city of Naples would be totaled by ash, gas, and the explosive impact if the nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted.

But of course, the impacts of a major eruption wouldn’t just be local. Wherever a large-scale eruption took place, airborne ash particles would clog up machinery and electrical components further afield, risking damage to power grids and possibly interrupting satellite communications.

On top of that, depending on the thickness of the emitted ash clouds, air-travel may grind to a halt over huge areas, as visibility and communications could be severely impacted. The effects of prolonged ash particle inhalation would also take its toll on humans and animals of surrounding nations, causing chronic lung diseases and making pre-existing conditions worse. But what about the issue that struck the people of 536 the hardest: famine? Unlike our ancestors of the 6th century, we have the benefit of longer-lasting food reserves, thanks to modern technology. For those able to stock up on non-perishables, starvation would be reasonably unlikely if the volcanic sun-block only lasted a single year. But a lack of fresh crops, triggered by a drop in global temperatures, would still cause economic strife as grain and produce prices skyrocketed. On top of this, the tiny ash particles sent up into the atmosphere by major volcanic eruptions could also prevent raindrops from forming inside clouds, leading to extreme droughts. Considering how water access continues to be an increasingly-severe issue in many places, a shift in the availability of this essential substance could prove catastrophic. In the already politically tense world we live in, it’s possible these additional tensions over the possession of vital, limited resources could push countries to the brink of even more war. Which is the last thing we need right now.So, with all those things considered, even with our wild-fires, coronavirus, and other chaos, compared to 536 A.D., 2020 could be a lot worse. At the very least, summer 2020 was pretty warm and sunny in most parts of the world, which definitely wasn’t the case back in 536. So, considering how much worse things could be, let’s just hope no sizeable volcanoes erupt any time soon.

If you were amazed at the worst year ever, you might want to read about

near-apocalypses we somehow survived. Thanks for reading.